The state of Kerala is brewing with controversy relating to the printing and sale of illegal lotteries. Every story relating to the issue has found its way to the front page of local newspapers and has become the topic of much debate between candidates contesting in the local body elections scheduled for this month.

Rumour has it that when a difference of opinion arose between the two promoters of Bhutan State Lottery – Monica Lottery Distributers and Martin Lottery Distributers, the former shadow-whistle-blew the latter’s irregularities. But as the controversy snowballed with the judgment of Justice P.R. Ramachandara Menon of the Kerala High Court, all interested parties buried the hatchet and fought against the judgment, which had restricted the number of lottery draws permissible in a week, to one.

Apart from rumours, there have been consistent news reports about Megha Lottery (sub-agent of Martin Lottery) printing illegal lottery tickets at Shivakashi and at other private printing presses. The law specifically stipulates that lotteries should be printed only at presses approved by either the Reserve Bank of India or the Indian Bankers’ Council. Taking note of these press reports along with the fact that the government of Bhutan had not renewed the agreement with Martin Lottery, but had appointed Monica Lottery as the new promoter, the state government refused to accept advance tax from Megha Lottery. Payment of advance tax under Section 10 of the Kerala Tax on Paper Lotteries Act, 2005, is an essential condition for the transport of printed lottery tickets into the state of Kerala.

The Congress-led opposition were up in arms against this refusal, since Monica Lottery had been appointed in March 2010, and the government had taken action only in September 2010, implying that Finance Minister, Thomas Issac, had permitted Megha to sell illegal lotteries during the intervening period.

Megha Lottery, faced with indirect prohibition on the sale of lotteries, approached the Kerala High Court for a writ of mandamus directing the government to accept the payment of advance tax. The government objected to the writ petition, contending that Megha was not a ‘Promoter’ of Bhutan State Lottery. The Single Judge (P.R. Ramachandara Menon, J.) of the Kerala High Court, after recording the submission of the government of Bhutan, that Megha was indeed its promoter, allowed the petition in part and directed the Kerala Government to accept advance tax to the extent permissible under sub-section 4(h) and sub-section 4(j) of the Lotteries (Regulation) Act, 1998, which was a Central legislation.

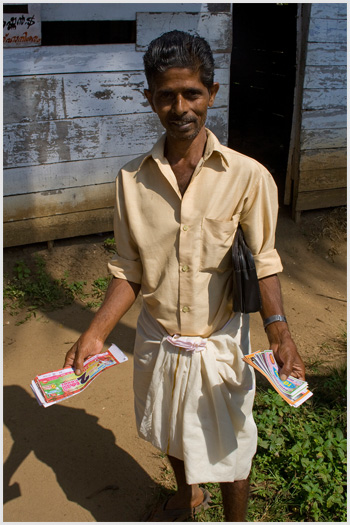

Sub-section 4(h) states that ‘no lottery shall have more than one draw in week’ and sub-section 4(j) states that ‘the number of bumper draws of a lottery shall not be more than six in a calendar year’. The Single Judge, relying on the aforesaid provisions in the 1998 Act, went on to say that the practice of conducting more than one lottery in a week under different schemes and different names was not permitted under the Act. According to the judge, sub-section 4(h) was incorporated in the statute to protect poor and illiterate people, who belong to the lower strata of society from the lure and glitter of becoming rich on a new dawn. The ‘cooling period’ of one week is provided to prevent such people from gambling with their life. Therefore, the promoters of lotteries were directed to furnish a statement showing the details of the draws (under all names or schemes, put together) to be conducted during the succeeding month under sub-section 10(1) of the state Act while remitting advance tax.

This judgment was challenged before the Division Bench of the Kerala High Court, both by the Kerala Government as well as by the Megha Lottery Agency. The Division Bench, consisting of Justices Thottathil B. Radhakrishnan and P. Bhavadasan, vacated the direction of the Single Judge restricting the number of lotteries per week. The Division Bench held that the state or its promoter was entitled to organise any number of lotteries and any kind of lotteries. According to the Division Bench, Section 4(h) of the Lotteries (Regulation) Act, 1998 did not have any impact on the number of lotteries or schemes the government could organise.

The Division Bench of the Kerala High Court held that it was the Central Government that is duty bound to ensure that no provisions of the rule or Act were violated. According to the court, any action against any lottery or promoter had to come from the Centre, although the state was not powerless in informing the Centre about such violations. The High Court also dismissed the appeal filed by the State Government and upheld the finding of the Single Judge that Megha was the promoter of Bhutan Lotteries, and issued a direction to the State Government to accept the advance tax from the promoter without any interest. The court observed that no special contract was required to engage a promoter to distribute the lottery. The court concluded that it was for the State and Union Governments to ensure that there were no violations of the Lotteries’ Regulation Act and other rules “so that vulnerable sections of society are not exploited through the temptations offered by lotteries.”

It requires no special legal dissection to understand that the judgment of the Division Bench of the Kerala High Court is rendered in blatant violation of statutory provisions. Although the judgment is apparently delivered to protect vulnerable sections of society from the temptations offered by the lotteries, the court has subtly helped the lottery tycoons by nullifying the statutory restriction imposed on the number of lottery draws permissible in a week. The State Government is expected to approach the Supreme Court, which may render finality in this issue.

The main drawback in the legal framework that regulates the conduct of lotteries is the absence of any power for the State Governments. Under the Central Act of 1998, a State government can either declare the entire state as a lottery-free-zone or let all the lotteries reign freely in the state. The reason for such restricted power is that state governments alone were permitted to organise and conduct lotteries and not private individuals. Therefore to prevent any unfair discrimination between competing state governments, the Central Act denied them powers of regulation.

In reality, it is not the state government, but their private promoters under the seal of the government, that are organising and selling lotteries. Although the State of Kerala has devised the mechanism of advance tax to indirectly regulate the conduct of foreign state lotteries and their promoters, the courts have consistently stuck down any positive action regulating their conduct, as the same is within the executive realm of the Central Government.

Therefore, in order to save the poor and ignorant of the society from being cheated through the sale of illegal lotteries, the Central Act of 1998 has to be amended granting appropriate powers to state governments to regulate conduct of lotteries organised by the private promoters.

P. Thomas Geeverghese is an advocate at the Kerala High Court.

The view expressed in this article are personal.