What obligations does the State have when it decides to outsource the exploitation of natural resources to private parties? To what extent – if at all – can courts enforce those obligations? These questions have come to the forefront over the last few years and are bound to dominate the political and legal landscape for some time to come. Two events, in particular, have contributed to this: the 2G Spectrum Scam, and the Coal block allocation scam, political controversies that rocked the previous government, and which were ultimately litigated before the Supreme Court. While the Court has reserved its judgment in the latter case, it issued between 2012 and 2014, an assortment of opinions in the former (“the Spectrum Cases”). These opinions go some way towards clarifying the present Court’s stance on these two questions and provide some guidance towards anticipating how future cases will be decided.

What obligations does the State have when it decides to outsource the exploitation of natural resources to private parties? To what extent – if at all – can courts enforce those obligations? These questions have come to the forefront over the last few years and are bound to dominate the political and legal landscape for some time to come. Two events, in particular, have contributed to this: the 2G Spectrum Scam, and the Coal block allocation scam, political controversies that rocked the previous government, and which were ultimately litigated before the Supreme Court. While the Court has reserved its judgment in the latter case, it issued between 2012 and 2014, an assortment of opinions in the former (“the Spectrum Cases”). These opinions go some way towards clarifying the present Court’s stance on these two questions and provide some guidance towards anticipating how future cases will be decided.

Simplifying greatly, the 2G Spectrum controversy arose out of the government’s decision to allocate spectrum to telecommunications companies on a first-come-first-serve basis. The entire process was rent with irregularities, such as an arbitrary advancement of the deadline for applications, and was duly challenged before the Court (the First Spectrum Case). The challenge itself, however, went far beyond simply impugning the specifics of the individual case: it invited the Court to rule on the standards generally applicable to government’s alienation, transference, or distribution of natural resources – a question of policy, if there ever was one. The Court accepted the invitation. It held that in distributing natural resources, “the State [is] bound to act in consonance with the principles of equality and public trust and ensure that no action is taken which may be detrimental to public interest.”

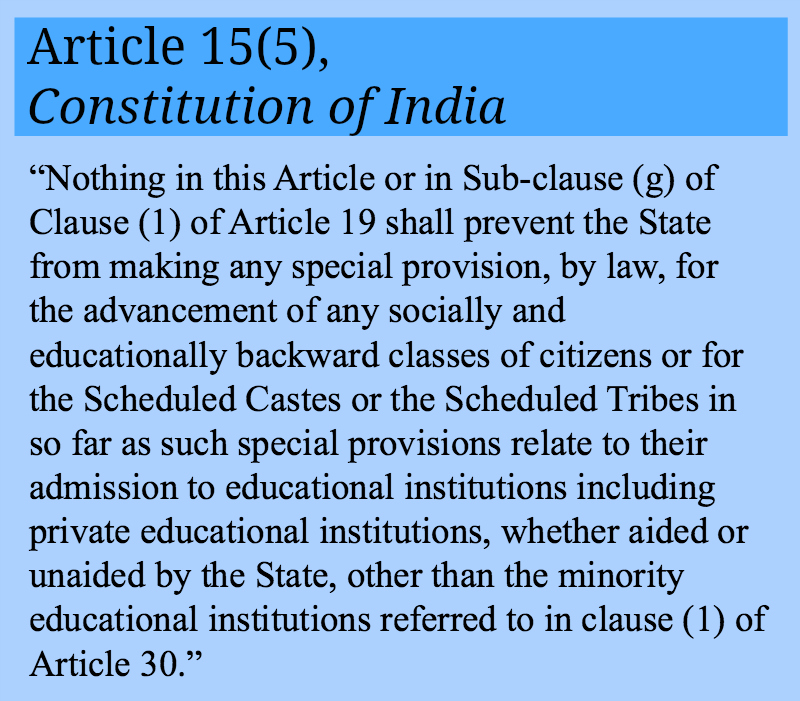

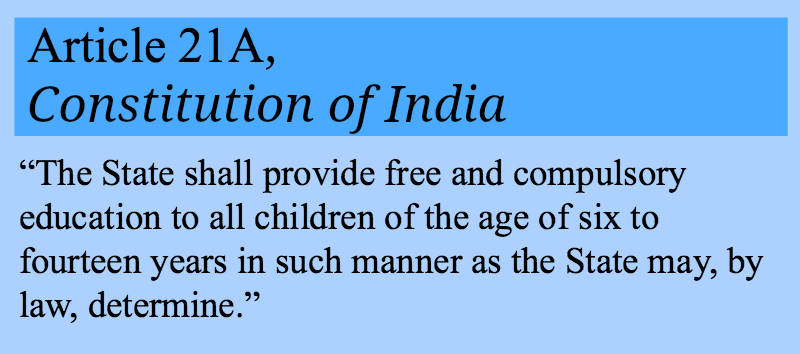

In the operative part of the Court’s opinion, these three principles – equality, public trust, and public interest (or common good) as obligations governing the State’s conduct – are repeatedly run together with little attention paid to the second important question: what is the Court’s institutional role in holding the State to these obligations? Equality, of course, is a constitutionally enforceable duty enforceable in the courts under Article 14. Additionally, the Court derived the doctrine of public trust (that is, in distributing natural resources, the State acts as a trustee for the people), and public interest or common good (whose difference from public trust is never satisfactorily explained) from Article 39(b), which is a non-enforceable Directive Principle of State Policy. Armed with this, the Court then held that “when it comes to alienation of scarce natural resources like spectrum etc., it is the burden of the State to ensure that a non-discriminatory method is adopted for distribution and alienation, which would necessarily result in protection of national/public interest… a duly publicized auction conducted fairly and impartially is perhaps the best method for discharging this burden and the methods like first-come-first-served when used for alienation of natural resources/public property are likely to be misused by unscrupulous people who are only interested in garnering maximum financial benefit and have no respect for the constitutional ethos and values. In other words, while transferring or alienating the natural resources, the State is duty bound to adopt the method of auction by giving wide publicity so that all eligible persons can participate in the process.”

In the operative part of the Court’s opinion, these three principles – equality, public trust, and public interest (or common good) as obligations governing the State’s conduct – are repeatedly run together with little attention paid to the second important question: what is the Court’s institutional role in holding the State to these obligations? Equality, of course, is a constitutionally enforceable duty enforceable in the courts under Article 14. Additionally, the Court derived the doctrine of public trust (that is, in distributing natural resources, the State acts as a trustee for the people), and public interest or common good (whose difference from public trust is never satisfactorily explained) from Article 39(b), which is a non-enforceable Directive Principle of State Policy. Armed with this, the Court then held that “when it comes to alienation of scarce natural resources like spectrum etc., it is the burden of the State to ensure that a non-discriminatory method is adopted for distribution and alienation, which would necessarily result in protection of national/public interest… a duly publicized auction conducted fairly and impartially is perhaps the best method for discharging this burden and the methods like first-come-first-served when used for alienation of natural resources/public property are likely to be misused by unscrupulous people who are only interested in garnering maximum financial benefit and have no respect for the constitutional ethos and values. In other words, while transferring or alienating the natural resources, the State is duty bound to adopt the method of auction by giving wide publicity so that all eligible persons can participate in the process.”

Non-discrimination under Article 14 and the public interest

This paragraph is worthy of close scrutiny. Essentially, the Court transforms what is meant to be an Article 14 enquiry (requiring the State to adopt a non-discriminatory method) into a public interest enquiry, by holding that non-discriminatory methods of distribution necessarily protect the public interest. It then substitutes its own vision of the public interest for that of the State’s, and holds that the only method consonant with that public interest is an auction (indeed, the Court expressly overrode the Telecome Regulatory Authority’s (TRAI) opinion in favour of a first-come-first-serve allotment by holding that TRAI could not “make recommendations which would deny people from participating in the distribution of national wealth and benefit a handful of persons.”)

Courts lack the institutional legitimacy and the competence to hold the government to some standards

The Court’s opinion is unfortunate, because it conflates the two very distinct questions that were outlined at the beginning of the essay. In finding that the government is bound by standards of equality, public trust and the common good, it automatically takes upon itself the task of determining the content of those standards, as well as their enforcement. This, however, is anything but obvious: there are many things that the State ought to do, which must be enforced at the ballot box, via social movements or elsewhere – but not in the courts. This is because one of two reasons might exist to prevent courts from ruling on the matter: reasons of institutional competence, and reasons of institutional legitimacy. Structurally, courts are not equipped and do not have the resources – that is, they lack the competence – to decide certain issues (such as, for instance, the allocation of resources in the national budget). Separately, as unelected bodies, courts have limited authority to interpret laws and protect constitutionally guaranteed rights – they cannot, for instance, frame policy, because that is something that the peoples’ elected representatives are exclusively authorised to do. For all its Article 14 gloss, the Court’s opinion arguably transgresses both these principles, and its failure to engage with them is doubly troubling.

The Government’s reaction was a Presidential Reference attempting to re-litigate the issue under the guise of seeking a clarification on the scope of the judgment. A Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court retreated from the expansive position taken in the first of the Spectrum Cases. In the Second Spectrum Case, it focused on the use of the word “perhaps” in the previous opinion (“an auction is… perhaps the best method…), to hold that the First Spectrum Case was limited to its facts, and did not lay down any general principles. Unfortunately, the Second Spectrum Case, like its predecessor, failed to engage with issues of institutional competence and legitimacy. Once again, it took refuge in the boundlessly manipulable category of Article 14 “arbitrariness” to hold that “when… a policy [of distribution of natural resources] is not backed by a social or welfare purpose, and precious and scarce natural resources are alienated to private entrepreneurs for commercial pursuits… adoption of means other than those that are competitive and maximise revenue may be arbitrary and face the wrath of Article 14.”

There are two ways of reading the above paragraph. One is that the Court, while narrowing the actual reach of the First Spectrum Case, has kept alive its overall import: public interest and the common good will determine what is or is not arbitrary under Article 14, and that determination ultimately vests with the Courts, to be exercised on a case to case basis. There is, however, another interpretation, which comes through in a subsequent paragraph: if the objective of a particular distribution is not directly social welfare or common good, but indirectly aims at that goal through maximising State revenue, then non-competitive methods will attract Article 14. For example, in the case of spectrum, if the government’s objective in allocating it to private parties is to maximise revenue (which it then – presumably – uses to further the common good), then a non-auction-based method violates Article 14. Notice that this is very close to the traditional Article 14 two-pronged test of intelligible differentia and rational nexus: clearly, differentiating spectrum applicants into those who applied before and after the cut-off date (first-come-first-served) bears no rational nexus with the purpose of revenue maximisation. Indeed, the Court seemed to be heading towards this conclusion (although it didn’t specifically make it), when it held in a subsequent paragraph: “Where revenue maximization is the object of a policy, being considered qua that resource at that point of time to be the best way to subserve the common good, auction would be one of the preferable methods, though not the only method. Where revenue maximization is not the object of a policy of distribution, the question of auction would not arise. Revenue considerations may assume secondary position to developmental considerations.”

The future development of the Court’s jurisprudence depends on which reading of the Second Spectrum Case – narrow or broad – is adopted by future Courts. In this essay, I’ve tried to suggest that it is the narrow reading – one that limits itself to a rigorous intelligible-differentia-rational-nexus Article 14 analysis – is truer to the institutional role of the Court.

Going beyond Article 14

In addition to the core arguments outlined above, the concepts of public trust and public good have played an additional role as background principle guiding the interpretation of legal provisions. In the Third Spectrum Case, a controversy arose over whether the Comptroller and Auditor General (“CAG”) was authorised to demand an audit of private telecom companies under its Article 149 powers. The key question was whether, in Article 149, the term “… any other authority or body”, that came after “Union” and “States” included purely private entities (which were therefore subject to a CAG audit). On a textual reading, it would seem that – on the principle of noscitur a sociis – the term was limited to bodies of a public or quasi-public character. The Court held, however, that “when the executive deals with the natural resources, like spectrum, which belongs to the people of this country, Parliament should know how the nation’s wealth has been dealt with by the executive and even by the UAS Licence holders. When nation’s wealth, like spectrum, is being dealt with by even the private parties, like service providers, they are accountable to the people and to the Parliament.” On a similar note, in Reliance Natural Resources Ltd. v. Reliance Industries Ltd., which involved an extremely complex dispute over the fixing of gas prices, the Court invoked the international law principle that a nations’ people have ultimate sovereignty over natural resources and the public trust doctrine, along with Articles 39(b) and (c) of the Constitution, to interpret Article 297 of the Constitution as prohibiting the State from entering “into a contract that permits extraction of resources in a manner that would abrogate its permanent sovereignty over such resources”, and that the State could not, inter alia, “transfer title of those resources after their extraction unless the [State] receives just and proper compensation.” These two cases demonstrate that Article 14 is not the only recourse available to the Court: it can use the public trust doctrine, and other similar concepts, as background principles to interpret constitutional and other provisions to conform to their requirements. How far it will go down that path before interpretation becomes invention, again, remains to be seen.

(Gautam Bhatia blogs at Indian Constitutional Law and Philosophy.)