In the second half of December 2014, the Supreme Court began to hear a series of challenges to various provisions of the Information Technology Act of 2008 (“IT Act”). Hearings will commence again when the Court reopens in January after the winter break. The batch of petitions, clubbed under Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, impugn – inter alia – the constitutional validity of Section 66A of the IT Act.

In the second half of December 2014, the Supreme Court began to hear a series of challenges to various provisions of the Information Technology Act of 2008 (“IT Act”). Hearings will commence again when the Court reopens in January after the winter break. The batch of petitions, clubbed under Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, impugn – inter alia – the constitutional validity of Section 66A of the IT Act.

Section 66A has attained a degree of notoriety in recent times, having been used to arrest people for posting (and liking) Facebook comments, for critical political speech, and so on. Section 66A is largely borrowed from the English Communications Act (the scope of which has been severely curtailed after allegations of abuse), and was originally intended to tackle spam and online harassment. It hardly bears repeating that its implementation has gone far beyond its objective. Beyond poor implementation, however, there is a strong case for the Court to hold at least part of Section 66A unconstitutional, on the ground that it violates the freedom of speech guarantee under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution.

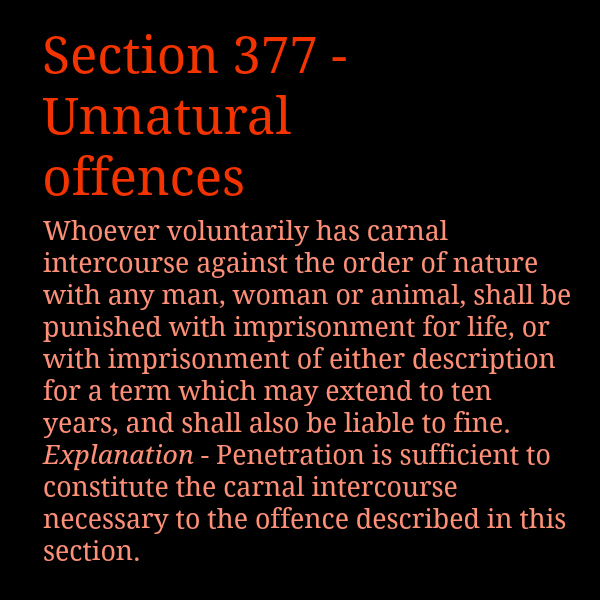

Among other things, Section 66A criminalises the sending, by a computer resource or a communication device, any information that is “grossly offensive” or has a “menacing character” (S. 66A(a)), as well as the sending of “any electronic mail or electronic mail message for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience.” The components of the offence, therefore, include online speech that is “grossly offensive”, “menacing”, or causes “annoyance” or “inconvenience”.

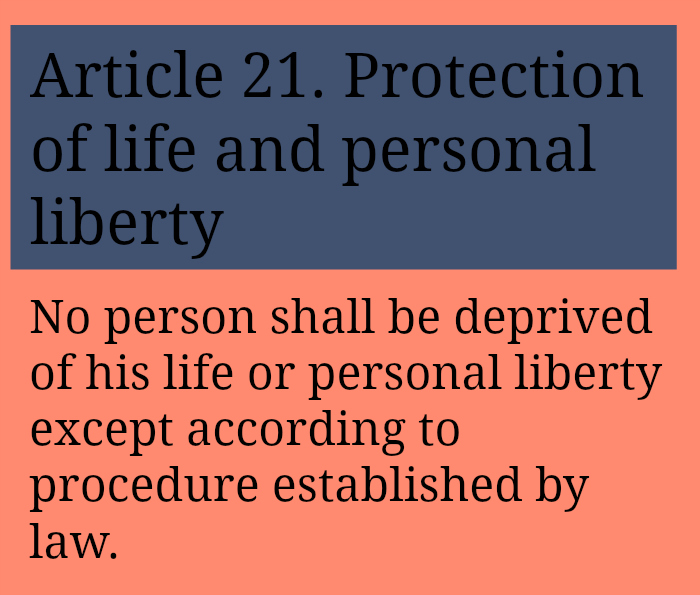

Legitimate restrictions permitted on the fundamental right in Article 19(1)(a)

The State’s authority to legitimately restrict speech can be sourced to Article 19(2) of the Constitution, which allows for the State to impose, by law, “reasonable restrictions on the freedom of speech in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence.” S. 66A’s restrictions might be connected with three of these concepts: public order, decency or morality, and defamation.

In a series of cases, the Supreme Court has made it clear that the connection between “public order” and a free speech restriction ought to be proximate, like that of a “spark in a powder keg”, and not far-fetched or remote. Clearly, while certain forms of offensive or menacing speech might, at some point, lead to a public order disturbance, the connection is anything but proximate. Similarly, the “decency and morality” prong has been invoked to deal with cases of obscenity, where the offending work appeals solely to the prurient interest, as seen from the point of view of the reasonable, strong-minded person. And lastly, the ingredients of defamation are highly specific, and much narrower than causing offence or annoyance – they are limited to lowering the reputation of the plaintiff in society (subject to certain defences).

Over-breadth and disproportionate restrictions

I t is therefore clear that certain terms of Section 66A suffer from the vice of “overbreadth”, that is, they authorise the restriction of expression that the government is entitled to prohibit, as well as that which it is not. In Chintaman Rao v. State of Madhya Pradesh, the Supreme Court, while striking down certain restrictions on agricultural labour under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution, held that “the law even to the extent that it could be said to authorize the imposition of restrictions in regard to agricultural labour cannot be held valid because the language employed is wide enough to cover restrictions both within and without the limits of constitutionally permissible legislative action affecting the right. So long as the possibility of its being applied for purposes not sanctioned by the Constitution cannot be ruled out, it must be held to be wholly void.” In other words, as far as fundamental rights are concerned, over-breadth is constitutionally fatal to a statute. This conclusion is further buttressed by the fact that in State of Madras v. V.G. Row, the Supreme Court also held that a “reasonable restriction” under Articles 19(2) to (6) would have to satisfy the requirements of proportionality: “the nature of the right alleged to have been infringed, the underlying purpose of the restrictions imposed, the extent and urgency of the evil sought to be remedied thereby, the disproportion of the imposition, the prevailing conditions at the time, should all enter into the judicial verdict.” Proportionality and over-breadth are closely linked: if a statute proscribes conduct that is much broader than what is permitted under Article 19(2), on the ground that there is some – tenuous – connection between the two, there is good reason to argue that the restriction is disproportionate.

t is therefore clear that certain terms of Section 66A suffer from the vice of “overbreadth”, that is, they authorise the restriction of expression that the government is entitled to prohibit, as well as that which it is not. In Chintaman Rao v. State of Madhya Pradesh, the Supreme Court, while striking down certain restrictions on agricultural labour under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution, held that “the law even to the extent that it could be said to authorize the imposition of restrictions in regard to agricultural labour cannot be held valid because the language employed is wide enough to cover restrictions both within and without the limits of constitutionally permissible legislative action affecting the right. So long as the possibility of its being applied for purposes not sanctioned by the Constitution cannot be ruled out, it must be held to be wholly void.” In other words, as far as fundamental rights are concerned, over-breadth is constitutionally fatal to a statute. This conclusion is further buttressed by the fact that in State of Madras v. V.G. Row, the Supreme Court also held that a “reasonable restriction” under Articles 19(2) to (6) would have to satisfy the requirements of proportionality: “the nature of the right alleged to have been infringed, the underlying purpose of the restrictions imposed, the extent and urgency of the evil sought to be remedied thereby, the disproportion of the imposition, the prevailing conditions at the time, should all enter into the judicial verdict.” Proportionality and over-breadth are closely linked: if a statute proscribes conduct that is much broader than what is permitted under Article 19(2), on the ground that there is some – tenuous – connection between the two, there is good reason to argue that the restriction is disproportionate.

Vagueness

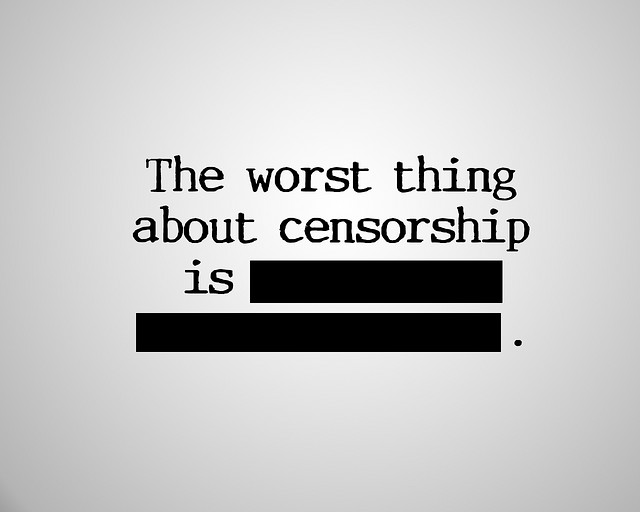

In addition to over-breadth, the provisions of Section 66A suffer from an additional problem: that of vagueness. “Menacing”, “annoyance”, “inconvenience” and “grossly offensive” are all highly subjective, and open to numerous varying interpretations depending upon individual and diverse standpoints. Their scope and boundary are both large and ill defined. Consequently, they create a zone of uncertainty for Internet users. What kind of speech might land you in trouble? It is hard to tell.

Vagueness is constitutionally problematic. In Kartar Singh v. State of Punjab, the Supreme Court – citing American precedent – observed that “it is the basic principle of legal jurisprudence that an enactment is void for vagueness if its prohibitions are not clearly defined. Vague laws offend several important values… laws should give the person of ordinary intelligence a reasonable opportunity to know what is prohibited, so that he may act accordingly. Vague laws may trap the innocent by not providing fair warning. Such a law impermissibly delegates basic policy matters to policemen and also judges for resolution on an ad hoc and subjective basis, with the attendant dangers of arbitrary and discriminatory application.” Thus, the twin problems of uncertainty and impermissible delegation to the executive, are inextricably connected with vague statutes.

Vague and over-broad statutes are especially problematic when it comes to free speech, because of the chilling effect that they cast upon speech. As the Court put it in Kartar Singh, “uncertain and undefined words deployed inevitably lead citizens to “steer far wider of the unlawful zone … than if the boundaries of the forbidden areas were clearly marked”.” When faced with uncertain, speech-restricting statutes, citizens are likely to self-censor, in order to ensure that they steer well clear of the prohibited line.

In the Shreya Singhal petitions, the Supreme Court will be faced with the choice of striking down Section 66A, or reading it down and (perhaps) issuing guidelines aimed at checking abuse. There is no doubt that the objectives of preventing scam and protecting Internet users against cyber-harassment and online bullying are important. But there are other parts of Section 66 that can be used to curtail such activities. If the Court is not minded to strike down Section 66A in its entirety, it ought to at least sever the words that have the greatest and most unbounded catchment area, and are most prone to abuse, and excise them from the statute.

(Gautam Bhatia blogs at Indian Constitutional Law and Philosophy.)