God exists and he too is a clown.

– Dario Fo

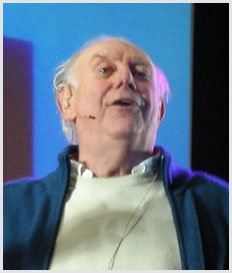

Dario Fo

Image above is from paolomariani69′s photostream on Flickr here and has been published under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

There is no denying Italians have a sense of humour. No, we are not talking about Berlusconi. Jokers get elected in many mature democracies, but arguably the most successful political farce of all time, Morte Accidentale di un Anarchico (Accidental Death of an Anarchist), was penned by an Italian – the Nobel Prize winner, Dario Fo. The play is based on a real-life incident of alleged anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli, who was accused of planting a bomb. He fell out of the window of the fourth floor of the police building where he was being interrogated. The Italian public, till date, remain sceptical of the official police version that he committed suicide or accidentally fell, owing to no fault of the policemen interrogating him. The incident, which transpired in December 1969, inspired Dario Fo, who was a successful left wing dramatist at that time, to write and produce the masterpiece in 1970.

The play is set in the police building where the death of the anarchist occurred, around a week after the incident. The scene opens with a serial impersonator, a self-confessed histrionic maniac, being interrogated by the police. He soon confuses the dim-witted policemen with his insane logic to the point where they realise it’s not worth the trouble to keep him detained. The “Maniac” however, intercepts a phone call and comes to know of the arrival of a judge to enquire into the ‘accidental’ death of the anarchist. The play progresses with the maniac impersonating the judge, and in the process, managing to expose the contradictions in the police story.

This play about police brutality and fallacy within the construct of the powerful continues to be relevant more than forty years after its creation, and the Maniac remains a dream role for every actor.

The play has slapstick, visual gags, double speak and allegorical sequences which successfully demystify the events relating to the death of the anarchist. With the maniac taking up different roles throughout the play, Fo employs a derivation of the mask technique often seen in Commedia dell’arte, a medieval theatre form having its origins in Italy. The play stands out as one of the few devoid of zoomorphic symbolism, an animal imagery often used to de-humanise existence and bring down authority figures from a pedestal: a staple in Fo works like Archangels don’t play Pinball, Mistero Buffo, La Storia della Tigre and Giullarate.

The play uses Verfremdungseffekt, a technique borrowed from Brecht, which is used in almost all the Fo works. An effect of alienation is brought about by the breaking of the fourth wall – by actors interacting with the audience often by dialogue or actions. It is an exercise aimed at the audience being constantly reminded of the performance as a play and reflecting upon it while the performance is on. The result is that as critic Antonio Scuderi puts it, “Often Fo’s farce leaves the audience not in laughter, but with unreleased anger”.

The historical and political background of the play has to be understood in the context of post-World War Italy. The axis of neo-fascist elements in the state machinery and outside, the Catholic Church and capitalistic agents, were active in their opposition to the rising influence of communism in Italy. A “strategy of tension” was covertly implemented to legitimise a state crackdown on the left wing elements by orchestrating a series of bombings, assassinations, and disruptive activities, which could then be attributed to the radical left. The Piazza Fontana bombing which Pinelli was accused of, was widely seen as a part of this strategy. The policemen involved, including Luigi Calabresi, who was later assassinated by the members of a left wing group, were cleared of all charges following an internal enquiry. The official narrative about the death or the suicide overwhelmed the mainstream media establishments. In this context, Accidental Death of an Anarchist is a true counter to hegemony in the Gramscian sense as moral neutrality was a luxury that Fo did not have.

Accidental Death of an Anarchist has been translated into more than forty languages, and it has been performed in many more countries. A peculiar feature of the play is its inherent scope to go beyond the literal translations and adapt to fit various political and cultural contexts. The play was adapted in India by various groups, of which Three-Star Operation, produced by Asmita Theatre, was highly successful. Accidental Death of an Anarchist, like all Fo plays, according to Fo himself, is meant to be performed and evolve with each performance. It is ironic, therefore, that Fo has been critical of many of the translations and adaptations of the play, including a version in English, directed and acted by Gavin Richards, who placed the play in a British setting in 1981.

(Ajith James is a graduate of the West Bengal National University of Juridical Sciences. This post was first published on myLaw.net here.)