Being an avid reader, I was excited when Amazon launched the Kindle and the Amazon bookstore in India. I started ‘buying’ a number of books from their bookstore, the most recent being the latest Dan Brown offering. The popularity of the book was obvious from the fact that a number of my friends asked me if they could borrow the book from me—now that I had a copy.

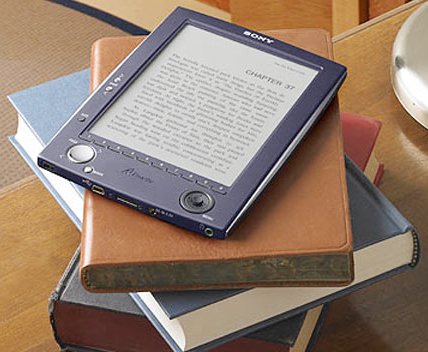

Image above is from Jorghex’s collection in Wikimedia Commons here and has been published under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unreported License.

Then came the conundrum. Could I lend the e-book to my friends? I could lend my Kindle itself, but could my friends download the e-book on their Kindles, as long as I gave permission? I felt I should be allowed to do that as ‘buying’ in the traditional sense would mean that I had the right to lend, and re-sell, to others.

To get an answer to my question, I visited the ‘help’ section on the Amazon website. This is the current policy—only certain books that are bought can be lent. Also, books can be lent only by US customers, and that too only for 14 days. As far as I can tell, Indian customers don’t have the right to lend books currently (or at least all the books I have bought can’t be lent). This means that I do not have the option to sell my e-book to a second hand bookstore or even lend to a friend who wants a copy (well I could, but that could amount to illegal activity).

So, in essence, when we ‘buy’ these e-books, we are not really buying these items, we are just given a license to use the contents in a certain manner. This got me thinking. If we are only being given a license to use this e-book, then why does the website display the message “Buy Now” when advertising and not “License Now”? Or “Buy the License to Read the Contents of this Book Now?” Not as catchy, and perhaps misleading to the consumer.

The Consumer Protection Act, 1986 (“COPRA”) is the main legislation in India that seeks to protect the interests of consumers. Interestingly, under the COPRA it is an offence for any person to use unfair means to entice and dupe customers who are generally not very well informed about both the product that they are buying, as well as the rights they have vis-à-vis that product.

In fact, the COPRA specifically allows consumers to file a complaint against any person who indulges in an ‘Unfair Trade Practice’. The term has a very long definition, but a few things caught my eye. Under the COPRA, the following acts are ‘Unfair Trade Practices’:

the practice of making any statement, whether orally or in writing or by visible representation which,

(i) falsely represents that the goods are of a particular standard, quality, quantity, grade, composition, style or model; ….. or

(vi) makes a false or misleading representation concerning the need for, or the usefulness of, any goods or services.

Additionally, misleading advertisements have also been interpreted by Indian Courts as an unfair trade practice, for example:

Society of Catalysts v. Star Plus T.V., IV (2008) CPJ 1 (NC): Here, a TV channel and mobile operator conducted a contest in which answers had to be sent by SMS. The advertisements claimed that there was no charge for participating in the contest. However, the SMS rates for sending answers were higher than usual SMS rates. So, the cost of participation was in fact built into the high SMS rates. The TV channel collected a large amount of funds, but distributed prizes for only part of the funds collected. This was held to be an unfair trade practice.

Cox & Kings (I)Pvt. Ltd. v. Joseph A. Fernandes, (2006) CPJ 129 (NC): In this case a cruise was advertised for 2 nights 3 days, however, the consumer effectively got only 1 night and 2 days. The advertisement was clearly deceptive and another example of an unfair trade practice.

Courts have however rarely taken up similar misrepresentations in the digital arena, and there is no case law to suggest how courts would view applications of these provisions in the digital paradigm. When a consumer goes to an online shopping site, they will never see these sites display a message such as ‘license music’ or ‘music license just a click away’. Rather, they always use the term ‘buy’ music or ‘buy’ e-books. In fact, a customer will likely never read the word ‘license’ until they take the time to go through the fine print in a ‘web policy’ or the ‘terms and conditions’ page.

Although not yet tested in the courts, looking at the purpose of the Consumer Protection Act, and the way courts have interpreted and enforced its provisions, there is a possibility that the practice of using the word ‘buy’ in online advertisements for shopping websites could be construed as an unfair trade practice under the COPRA. Especially in newer markets like India, online websites must be careful while selling products to consumers to ensure that there are no deceptive or misleading advertisements that induce a customer to believe that they are actually buying the product in the sense they are used to, as opposed to just a license to view or listen to the material!

(Deepa Mookerjee is a member of the faculty at myLaw.net.)