A terse ruling by the United States Supreme Court in Shenk v. United States (1919) contains a powerful metaphor on legal arguments about the freedom of speech and expression. “The most stringent protection of free speech”, Justice Holmes said speaking for the Court, “would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic”. Even though the Court has since moved away from it as a legal standard (Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969)), it continues to clearly illustrate the idea that the freedom of speech and expression is a conditioned right subject to constitutional limitations. For instance, the Supreme Court of India quoted Justice Holmes in the Ramlila Maidan Incident Case (2012).

A terse ruling by the United States Supreme Court in Shenk v. United States (1919) contains a powerful metaphor on legal arguments about the freedom of speech and expression. “The most stringent protection of free speech”, Justice Holmes said speaking for the Court, “would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic”. Even though the Court has since moved away from it as a legal standard (Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969)), it continues to clearly illustrate the idea that the freedom of speech and expression is a conditioned right subject to constitutional limitations. For instance, the Supreme Court of India quoted Justice Holmes in the Ramlila Maidan Incident Case (2012).

Original limitations on free speech

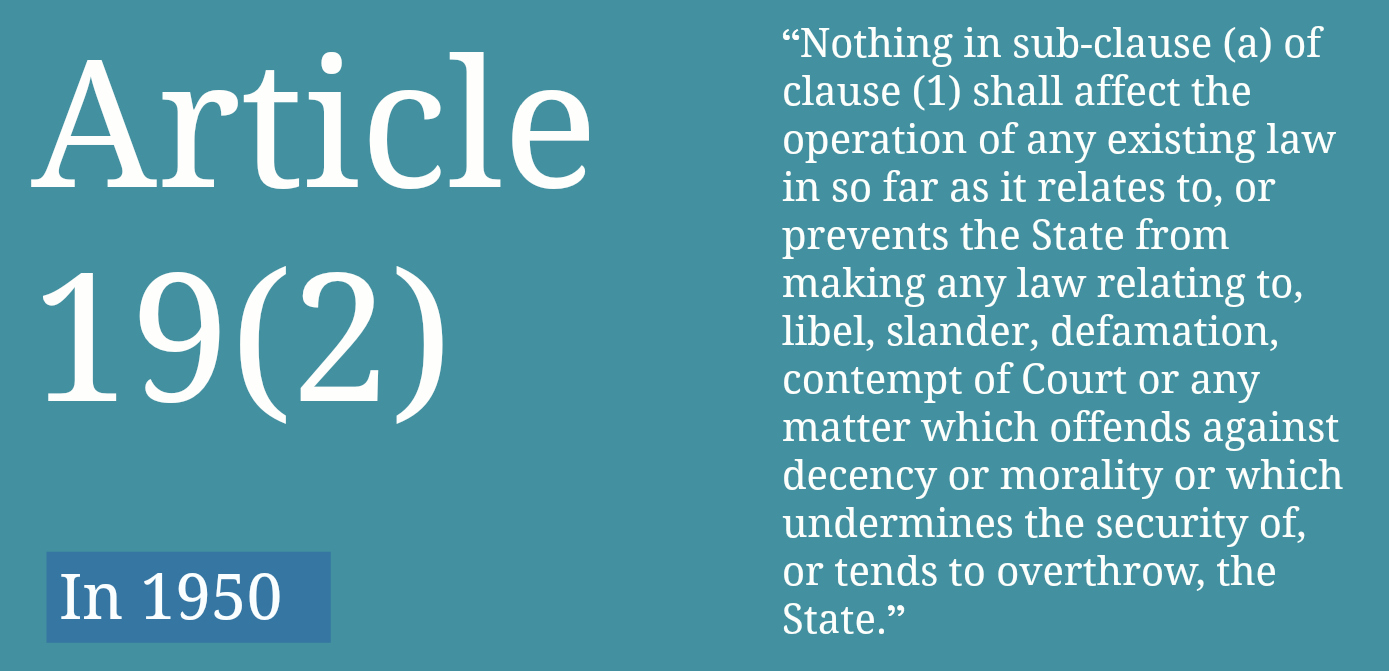

The Constitution of India (“Constitution”) follows this scheme and provides a conditioned right to the freedom of speech and expression. Article 19(1)(a) provides for the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression and Article 19(2) places restrictions on it. Known as “reasonable restrictions” today, they permitted the legislature to make enactments that fall within the grounds enumerated under it.

The ink had not dried on the Constitution when petitions were filed in various courts testing the extent of some laws that criminalised speech. While gauging the validity of such laws, the Supreme Court was called in to interpret Article 19(2).

The ink had not dried on the Constitution when petitions were filed in various courts testing the extent of some laws that criminalised speech. While gauging the validity of such laws, the Supreme Court was called in to interpret Article 19(2).

Petitions challenging public order statutes

The Supreme Court interpreted the scope of Article 19(2) as it stood originally in two batches of petitions before it — Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras (1950) and Brij Bhushan v. State of Delhi (1950). In Romesh Thapar, the Court held parts of the Madras Maintaince of Public Order Act, 1949 to be beyond the ambit of the grounds contained in Article 19(2) and struck them down as unconstitutional. On similar reasoning, Brij Bhushan held pre-censorship orders issued under the East Punjab Public Safety Act, 1949 to be unconstitional. Justice Fazal Ali dissented persuasively in both cases, arguing that the enactments fall within the ambit of Article 19(2). H.M. Seervai, citing the presumption of constitutionality, has agreed with his views.

Some High Court judgments also did what the Supreme Court did. For instance, the crime of sedition and the Press (Emergency Powers) Act, 1931 were held unconstitutional. These petitions set the stage for the Parliament of India to consider the first amendment to the Constitution of India.

The 1st Amendment

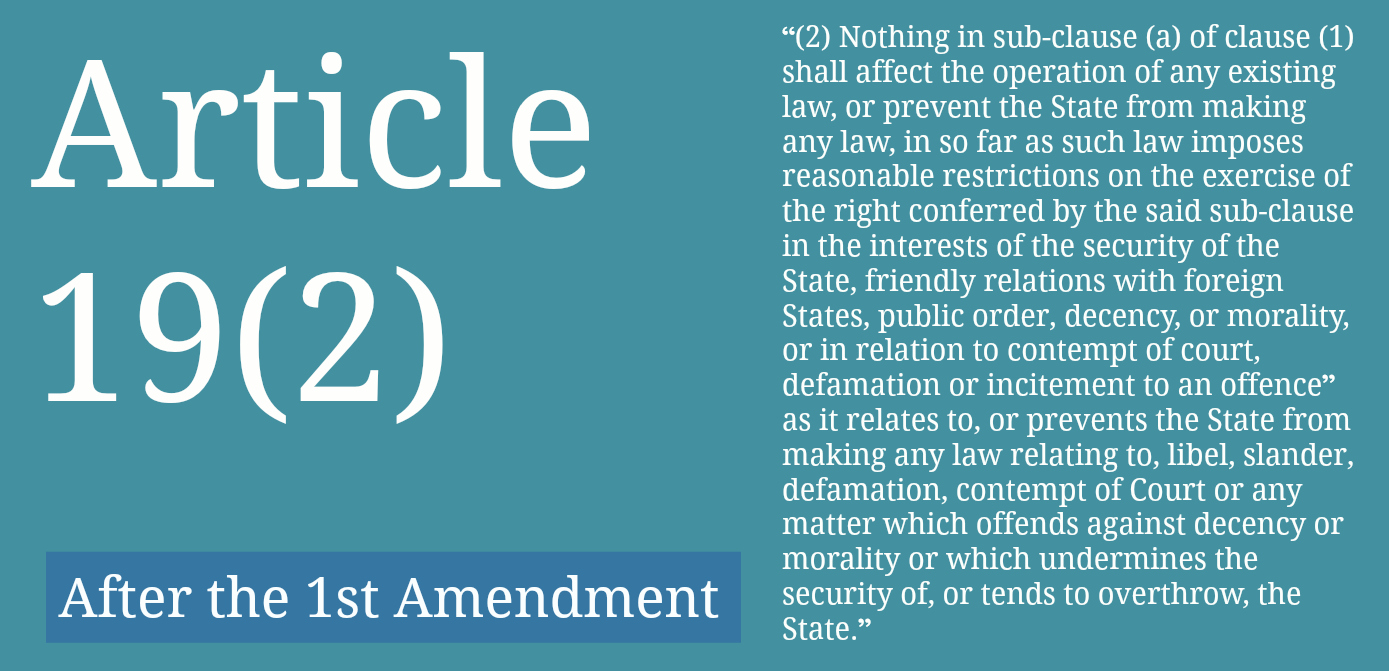

On May 16, 1951, a mere sixteen months after the Constitution was adopted, a bill to amend it was introduced in the Parliament. The 1st Amendment Bill stated that “…Article 19(1)(a) has been held by some courts to be so comprehensive as not to render a person culpable even if he advocates murder or other crimes of violence” and sought to amend and expand Article 19(2). Importantly, the word, “reasonable” was inserted in the Bill after a Select Committee report was adopted on May 29. Article 19(2) was then amended by the Constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951.

The Supreme Court was considerably accommodative in the constitutional appraisal of laws alleged to be in conflict with the amended Article 19(2). In Ramji Lal Modi v. State of Uttar Pradesh (1957), the constitionality of Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, which contained the offence of insulting a religion, was challenged. The provision was in the news recently when publisher Penguin India claimed that the threat of prosecution for this offence was the reason it withdrew a book by Wendy Doniger.

Analysing it, the Court held that “the expression ‘in the interests of’ occurring in the amended Cl. (2) of Art. 19 had the effect of making the protection afforded by that clause very wide and a law not directly designed to maintain public order would well be within its protection if such activities as it penalised had a tendency to cause public disorder.” With the passage of time, there has been growing recognition that Article 19(2) as amended, was framed for the convenience of a police constable and not for the liberty of artists, writers, and citizens.

The necessity of reasonable restrictions

Even though the Supreme Court has not struck down many such laws as unconstitutional, it has often limited their operation by reading requirements into them. The scope of Article 19(2) has been considerably expanded and cases such as Romesh Thappar and Brij Bhushan are no longer good law but the judiciary has often seized upon the requirement of “reasonableness” in support of these limitations. Take the example of the cases on sedition, an offence contained in Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

The Supreme Court in Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar (1962), while holding the provision to be constitutional, placed several limitations on it by holding that only those acts that had the intention or tendency to incite public disorder or violence would invite prosecution. The Court noted that it was clear that “criticism of public measures or comment on Government action, however strongly worded, would be within reasonable limits and would be consistent with the fundamental right of freedom of speech and expression.”

This sentiment can also be seen in the recent case of Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan v. Union of India and Others (2014), where it refused to issue directions for increased penal sanctions against ‘hate speeches’. The Court asked the Law Commission of India to study the applicable law and said, “It is desirable to put reasonable prohibition on unwarranted actions but there may arise difficulty in confining the prohibition to some manageable standard and in doing so, it may encompass all sorts of speeches which needs to be avoided .”

However, given that every few weeks, the Press highlights instances of the egregious abuse of these provisions, many have questioned the effectiveness of these court crafted doctrines and limitations.

The way forward

The prosecutions of Binayak Sen, cartoonist Aseem Trivedi, and the Kashmiri students at Swami Vivekanand Subharti University present a mismatch in the doctrinal limitations imposed by Court precedent and the prosecutions that disregard them. These errors are corrected, if ever, through the appeals process but not before a punishment is visited in the form of pre-trial detention or even by the harassment caused by the prosecution itself. The Supreme Court’s precedent seeks to limit the application of such penal provisions but it is often disregarded at the stage of trial. This experience makes a strong case for their amendment or repeal. Though inconvenient given the current state of our polity, the proper forum for arguments about changing laws affecting speech and expression in India is the floor of the Parliament, not the Chief Justice’s court.

A concluding caveat on the arguments to amend Article 19(2) itself, rather than delete specific penal laws. Article 19(2) only provides an outer limit for legislation and not a constitutional imperative for the enactment of reasonable restrictions on speech. Today, the vast expanse of our penal laws not only prevent false fire alarms in cinemas but even criminalise the screening of movies. The time is ripe for the Law Commission of India to study how the laws that limit speech and expression are defined by their abuse and intolerance of dissent.

Apar Gupta is a partner at Advani & Co., and was recently named by Forbes India in its list of thirty Indians under thirty years of age for his work in media and technology law.