India has many laws that are over a hundred years old. Several of them have lost their relevance over time for various reasons, either due to a change in circumstances, or because the original objectives that these laws served have been achieved, or because they have been subsumed under more recent legislation. The old laws however, continue to remain in the statute book, causing confusion by adding to the ever-expanding maze of statutes that govern us, and creating scope for abuse.

Weeding out obsolete laws has become a priority for the present government. In August 2014, it set up a committee to identify obsolete laws and make recommendations for their repeal. How have we fared till now and what else needs to be done to put a streamlined process in place for spring-cleaning these laws?

The age of laws in India

The list of central laws maintained by the Union Law Ministry features 1,138 current statutes without taking into account the large number of Appropriation Acts and Amendment Acts that are also part of the statute book. As estimated by the P.C. Jain Commission in 1998, there are also about 25,000 to 30,000 state laws.

An examination of the ages of the existing central laws brings out some interesting facts. Of the 1,138 listed laws, 298 date back to the pre-Independence era. 140 of them are from the 1800s. While vintage by itself does not signify redundancy – the Indian Contract Act, 1872 and the Indian Penal Code, 1860 are clear examples – it does signal a need to rethink the relevance of these laws in light of changing social and economic contexts. In the case of state laws, the absence of a comprehensive database makes it difficult to conduct a similar assessment of their number and antiquity.

Since many of the pre-Independence laws also fall under subjects that are now within the exclusive legislative competence of the states, state legislatures are responsible for their repeal. Better co-ordination is therefore required between the Union and the states on this issue.

Identifying dead wood

Of the types of laws that are in need for immediate repeal, the most obvious are the Amendment Acts, (that is, laws that were originally intended to amend or change the text of a parent statute, and which changes have already been incorporated) and Appropriation Acts (that is, laws that were meant to operate for a fixed period that has since expired).

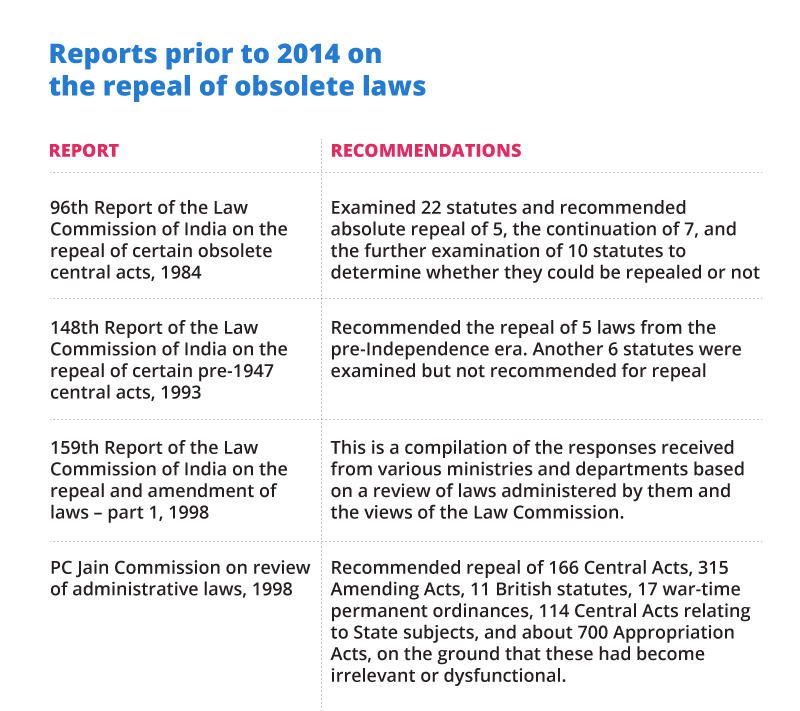

The Law Commission has undertaken a number of exercises to help identify the ‘dead wood’ that needs to be removed from the statute book. The 1998 PC Jain Commission also made recommendations on this subject (See table below). While many of the identified laws have already been repealed, 253 statutes remain, which have been identified for repeal, but on which action is still awaited from the government (Appendix II, Law Commission of India, 248th Report).

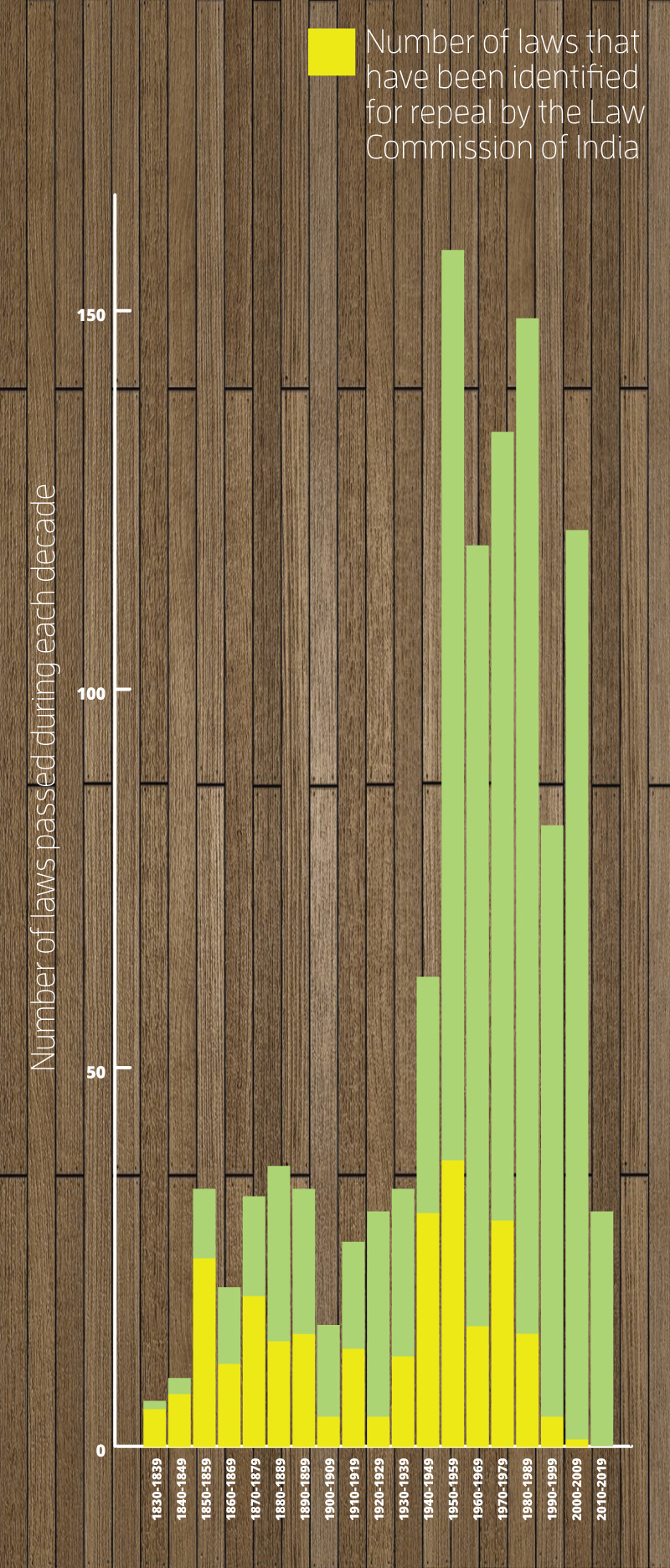

In 2014, the Law Commission undertook the detailed exercise of classifying all laws into 49 subject-categories and then identifying those laws that were in need of repeal. The four-part series of interim reports released by the Commission identifies a total of 265 laws that need to be repealed. The image below represents for each decade, the number of existing laws and the number of laws that have been recommended for repeal by the Law Commission.

Following these reports, the Legislative Department at the Ministry of Law and Justice sought the views of various departments regarding the proposed repeals. Two Repealing and Amending Bills have already been placed before the Parliament to give effect to the repeal of 126 laws that have “either ceased to be in force, have become obsolete or their retention as separate Acts is unnecessary”. Almost all of these are Amendment Acts.

Spring-cleaning the statute book

How do we ensure that the statute book keeps pace with changing times? One option followed by countries like United States and Canada is to have a “sunset clause” which sets out upfront, an expiry date for a law. In practice however, sunset clauses are often treated as a “snooze button” with the laws being extended as a matter of course. The more immediate solution may be to mandate the Law Commission or another body to undertake a statutory review exercise on a regular basis. This is crucial for both central as well as state laws. However, our experience from the past has been that such reviews do not always lead to their logical end, mainly because of legislative inaction. While introducing any system of regular review therefore, it is necessary to ensure that central and state legislative departments are made responsible for formulating draft bills based on these suggestions. Finally, of course, it is up to the Parliament and the State Legislatures to recognise their responsibility to clear the statute book of redundant and conflicting laws.

(Sumathi Chandrashekaran and Smriti Parsheera are lawyers working in the area of public policy.)