While many legal experts have expressed their views on the process proposed for the appointment of judges to the Supreme Court and the high courts under the Constitution (121st Amendment Bill), 2014, (“proposed constitutional amendment”) and the National Judicial Appointment Commission Bill, 2014 (“NJAC Bill”), there have not been many detailed clause-by-clause analyses.

While many legal experts have expressed their views on the process proposed for the appointment of judges to the Supreme Court and the high courts under the Constitution (121st Amendment Bill), 2014, (“proposed constitutional amendment”) and the National Judicial Appointment Commission Bill, 2014 (“NJAC Bill”), there have not been many detailed clause-by-clause analyses.

Since the proposed constitutional amendment must be ratified by the legislative assemblies of at least 15 of the 29 states under the proviso to Article 368(2) of the Constitution of India, a process that is likely to take at least six months, substantive challenges to the amendment and the NJAC Bill are only likely to take shape next year. On August 25, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court, comprising Justices Dave, Chelameswar, and Sikri had refused to entertain the first round of challenges brought at the current stage by some petitioners including the Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association. The Court left it open for the parties to challenge the amendments and the legislation when they come into force. Legal practitioners and academics therefore, have enough time to examine the proposed provisions and their legality. Here, I will discuss the possible grounds of challenge to the proposed constitutional amendment.

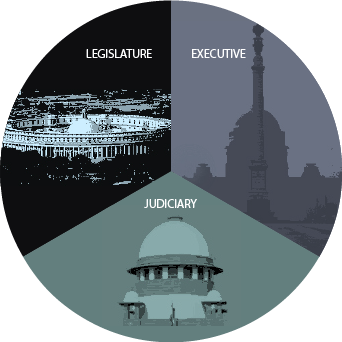

In India, a constitutional amendment can be legally tested on two sets of grounds. The first are the procedural grounds, which relate to procedural aspects such as whether the amendment was passed with the required majority of the concerned legislative houses as prescribed in Article 368 of the Constitution. Second and more important are the substantive limits on the Parliament’s power to amend what have been described as the “basic structure” or the “basic features” of the Constitution.

As all Indian students of law are aware, the “basic structure” or the “basic features” doctrine was first proposed by the Supreme Court in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, AIR 1973 SC 1461, where out of thirteen judges of the Supreme Court, seven held that the amending power of the Parliament in respect of the Constitution was not unlimited. The Court held that a constitutional amendment that damages the basic structure or the basic features of the Constitution is beyond the constitutive power of the Parliament. Even though the Supreme Court gave a few examples of the constitutional principles that are part of the basic features of the Constitution, no exhaustive list was provided and subsequent judgments of the Court have illustratively developed on the principles that are part of the basic structure or the basic features.

The basic structure doctrine was sought to be undone by the Parliament within three years, by passage of the Constitution (42nd Amendment) Act, 1976. By this amendment, Clauses (iv) and (v) were inserted in Article 368 of the Constitution. These two clauses provided that no amendment of the Constitution can be called in question in any court on any ground and that there will be no limitation on the constituent power of the Parliament. In Minerva Mills v. Union of India, AIR 1980 SC 1789, a constitution bench of the Supreme Court struck down these two clauses because they violated the basic structure doctrine. With the decision in Minerva Mills, the basic structure doctrine has come to stay in Indian constitutional law.

The principle of judicial independence is part of the Constitution’s basic structure

Assuming that there are no procedural lapses in the passage and ratification of the proposed constitutional amendment, the challenge before the Supreme Court will focus on whether the constitutional amendment or any of its provisions violate any part of the basic structure of the Constitution. The obvious parts of the basic structure that the proposed constitutional amendment will be tested on are “separation of powers” and “independence of judicary”. The Supreme Court has observed in several judgments that these two principles are part of the basic structure of the Constitution. Many legal experts have however, pointed out that the content of “independence of judiciary” as a part of the basic structure has not been defined and so it will not be easy for the Supreme Court to set aside the proposed constitutional amendment on the touchstone of this basic structure doctrine.

In my view, this analysis is incorrect. At least on three occassions, the Supreme Court has set aside constitutional amendments because in its view they violated the basic structure principle of the independence of judiciary. In P Sambamurthy v. State of Andhra Pradesh and Another, (1987) 1 SCC 362, a constitution bench of the Supreme Court set aside the proviso to Clause 5 of Article 371-D of the Constitution, which conferred on the state government, the power to modify or annul the final order of an administrative tribunal. This constitutional provision was found to violate the principle of independence of judiciary and was thus held to be beyond the constitutive or amending power of the Parliament. In Kihoto Hollohan v. Zachillu and Others, (1992) Supp 2 SCC 651, a constitution bench of the Supreme Court held that Paragraph 7 of Schedule X of the Constitution, which excluded the jurisdiction of all courts including the Supreme Court under Article 136 and the high courts under Articles 226 and 227 on any matter regarding the disqualification of a member of Parliament or state legislature on account of defection, violated the basic structure principles of independence of judiciary and the separation of powers. In L. Chandrakumar v. Union of India, (1997) 3 SCC 261, a seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court held that Articles 323-A(2)(d) and 323-B(3)(d), which empowered the Parliament and the state legislatures to exclude the jurisdiction of all courts except the Supreme Court under Article 136, was violative of the basic structure principle of judicial review, which was crucial for maintaining the independence of the judiciary.

These cases show that the Supreme Court has not been shy about setting aside constitutional provisions on the touchstone of judicial independence as a basic feature. The Supreme Court’s approach has not been to evolve any standard or well-defined test to determine what constitutes judicial independence. Instead, the Court has followed a case-by-case approach in determining whether a specific constitutional amendment interferes with the independence of the judiciary, somewhat similar to the “you know it when you see it” test used in some other contexts. In light of this history, it would be very likely that the Supreme Court will set aside any provisions in the proposed constitutional amendment that seeks to interfere with independence of judiciary.

How the proposed constitutional amendment violates judicial independence

The proposed constitutional amendment amends the current Article 124 so that the President shall appoint the judges of the Supreme Court and the High Courts on the recommendation of the National Judicial Appointment Commission (“NJAC”). The new Article 124A provides the composition of the NJAC. It requires the total of six members which includes the Chief Justice of India, two seniormost judges of the Supreme Court, the Union Minister of Law and Justice, and two “eminent persons” to be nominated by a three member panel comprising of the Prime Minister, the Chief Justice of India, and the leader of the largest single opposition party in the Lok Sabha. Interestingly, Clause 2 of Article 124A provides that no act or proceeding of the NJAC shall be invalidated on the ground of the existence of a vacancy or defect in the constitution of the NJAC.

In my view, this composition of NJAC comprising of only three judges out of the six members and the fact that the “eminent persons” can be nominated by a predominently political committee (comprising a majority of the Prime Minister and Opposition Leader, with the Chief Justice in a minority), leads to the real possibility that the two eminent persons can be made to act as extensions of the government. Even a candidate with the complete backing of the three judicial members can be effectively vetoed by the government for political reasons. This, prima facie, seems to interfere with the independence of the appointmenrt process for Supreme Court judges.

Further, Clause 2 of Article 124A would, in all likelihood, be set aside because it leaves open the possibility that valid recommendations can be made by NJAC even when all the three Supreme Court judges do not participate in that decision-making process.

The proposed constitutional amendment also seeks to replace the role of the Chief Justice of India under Artices 127 and 128 with that of NJAC. Collectively, these amendements seek to replace the role envisaged for the Chief Justice of India and the other judges of the Supreme Court in the original Constitution, with the NJAC, which as explained above, is a body capable of making its decision on political considerations. It is highly likely that the Supreme Court will view these far reaching changes as an assault on its hard earned independence from the political executive. Depoliticisation of the judicial appointment process has been substantially responsible for the proactive role played by the higher courts in exposing corruption even in high places in the government and passing a whole range of judgments in the public interest. There is also therefore, great public interest in retaining a fully depoliticised judicial appointment process.

In so far as the appointment procedure for high court judges is concerned, the proposed constitutional amendment seeks to amend Articles 217, 222, and 224 of the Constitution, giving the NJAC, the power to appoint and transfer high court judges. This power is currently exercised by a Supreme Court collegium in consultation of the Chief Justice of the concerned high court. Apart from the problems identified in relation to the appointment of Supreme Court judges, giving the power to transfer high court judges to the NJAC, a body capable of being politically influenced, can wreak havoc on the independence of decision-making by high court judges, particularly when deciding crucial cases against the government. Transfers can be used to punish high court judges who do not toe the line of the government of the day.

Needless to say, the whole issue of judicial independence will be examined by the Supreme Court through the prism of the factual situation prevailing in India. Unlike in many western countries, the central and state governments are major litigants before the High Courts and the Supreme Court. By some estimates, the governments are involved in more than half of all litigation in the country. It is unlikely that the Supreme Court is going to miss the conflict of interest of having one of the major litigants before it influence and in some cases even determine, its composition.

Supreme Court will also have to deal with the flaws of the collegium system

However, if the Supreme Court chooses to strike down the proposed constitutional amendments, it must necessarily, at the same time, address the issue of transparency in the current collegium system. Ironically, neither the proposed constitutional amendments nor the NJAC Bill deal with the primary criticism of the collegium system, which is the complete lack of transparancy in the appointment process. Instead, they merely seek to give the government of the day, a voice and possibly a decisive one, in a non-transparent machanism of appointment. If the Supreme Court was to strike down the proposed constitutional amendment, to maintain the legitimacy of its decision, it must necessarily in the judgment, lay down in detail, binding guidelines on the process of the decision making to be followed by the collegium, including the broad criteria for elevation to the Supreme Court, which will give both the members of the Bar and the public at large, a sense of confidence that only the best, most honest, hard working, and principled judges are holding office in the higher courts of our republic.

However, if the Supreme Court chooses to strike down the proposed constitutional amendments, it must necessarily, at the same time, address the issue of transparency in the current collegium system. Ironically, neither the proposed constitutional amendments nor the NJAC Bill deal with the primary criticism of the collegium system, which is the complete lack of transparancy in the appointment process. Instead, they merely seek to give the government of the day, a voice and possibly a decisive one, in a non-transparent machanism of appointment. If the Supreme Court was to strike down the proposed constitutional amendment, to maintain the legitimacy of its decision, it must necessarily in the judgment, lay down in detail, binding guidelines on the process of the decision making to be followed by the collegium, including the broad criteria for elevation to the Supreme Court, which will give both the members of the Bar and the public at large, a sense of confidence that only the best, most honest, hard working, and principled judges are holding office in the higher courts of our republic.

(Shadan Farasat is an Advocate-on-Record at the Supreme Court of India)