By Ajay J.N.

Two decisions of the Supreme Court, both by the same bench comprising Justices Markandey Katju and Asok Kumar Ganguly, recommended limiting the use of interim injunctions in intellectual property rights (“IPR”) matters.

Shree Vardhman Rice and General Mills v. Amar Singh Chawalwala, (2009) 10 SCC 257 pertained to an appeal against an order of the trial court on an interlocutory application for injunction for trademark infringement. The court, while declining to interfere, held:

“3. Without going in to the merits of the controversy, we are of the opinion that the matters relating to trademarks, copyrights and patents should be finally decided very expeditiously by the Trial Court instead of merely granting or refusing to grant injunction. Experience shows that in the matters of trademarks, copyrights and patents, litigation is mainly fought between the parties about the temporary injunction and that goes on for years and years and the result is that the suit is hardly decided finally. This is not proper.

“4. Proviso (a) to Order XVII Rule 1(2) C.P.C. states that when the hearing of the suit has commenced, it shall be continued from day-to-day until all the witnesses in attendance have been examined, unless the Court finds that, for the exceptional reasons to be recorded by it, the adjournment of the hearing beyond the following day is necessary. The Court should also observe Clauses (b) to (e) of the said proviso.

“5. In our opinion, in matters relating to trademarks, copyright and patents the proviso to Order XVII Rule 1(2) C.P.C. should be strictly complied with by all the Courts, and the hearing of the suit in such matters should proceed on day to day basis and the final judgment should be given normally within four months from the date of the filing of the suit.”

In Bajaj Auto Limited v. TVS Motor Company Limited, (2009) 9 SCC 797, the same bench, while quoting the decision in the Shree Vardhman Rice and General Mills Case, (supra) observed:

“10. In the present case, although arguments were advanced at some length by the learned Counsel for both the parties, we are of the opinion that instead of deciding the case at the interlocutory stage, the suit itself should be disposed of finally at a very early date.”

These decisions may seem innocuous, but may prove to be a panacea for defendants in intellectual property matters. In a recent case before the Karnataka High Court, the defendant’s sole contention before the High Court in appeal against the grant of interlocutory injunction was in terms of these Supreme Court decisions; the High Court was not too impressed and dismissed the appeal, but also directed the trial court to dispose of the matter in four months.

On closer examination, the decision in the Shree Vardhman Rice and General Mills Case does not state that temporary injunctions should not be granted in all matters but the implication is that the final disposal should be given importance and not the grant of temporary injunction. More recently, on September 27, 2010, in another matter involving interlocutory injunctions, the Supreme Court refused to entertain the matter and directed the high court to dispose the main matter within nine months. (See, Raymond Limited v. Raymond Pharmaceuticals Ltd., in SLP (Civil) No(s).26610/2010). From these decisions, the philosophy of the Supreme Court appears to be ‘let us not interfere in interlocutory applications in IPR matters’. Let us examine the implication of such an approach.

Temporary injunctions in IPR litigation – A sine-qua-non

If the courts adopt a strategy of not granting a temporary injunction, the impact of such a decision would be enormous and would change the entire nature of intellectual property litigation in India. Temporary injunctions are necessary to protect the plaintiff’s rights during the pendency of the suit, and the impact of non-grant of injunction is enormous. In actions pertaining to passing off or infringement in patents, trademarks, or designs matters, it is very important that the injunction be granted before the defendant can establish a considerable market presence during the pendency of the suit and render the very filing of the suit infructuous. Similarly, in the case of disparaging marks, the damage will be done by the time the suit is decreed. In the case of copyright or a breach of confidence concerning literature, music, cinema or even software, or in matters of piracy, the urgency is tremendous. Once the copyrighted matter is communicated to the public for a long duration, it becomes difficult to minimise the impact. Pirated materials are easily disposable, cannot be accounted for, and the damages cannot be calculated in terms of money.

Under Section 135 (2) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999, the Court has the discretion to grant ex-parte orders, which would in effect, be taken away by such a decision from the Supreme Court. The various injunctions which can be granted during the pendency of the trial include those for discovery of documents, preservation of infringing goods, documents or other evidence which are related to the subject-matter of the suit and restraining the defendant from disposing of or dealing with his assets in a manner which may adversely affect the plaintiff’s ability to recover damages, costs, or other pecuniary remedies which may finally be awarded. If there is a blanket ban on the grant of interim orders, the conduct of the trial becomes difficult, resulting in unfair prejudice to the plaintiff, and the very purpose of the enactment would be lost.

Very often, the grant or non-grant of temporary injunction results in the matter being settled. The defendant may not want to fight the litigation, and if the plaintiff does not get the injunction, he may want to close the matter immediately.

If an injunction is not granted, then the remedy lies in damages. However, India is yet to develop the concept of award of exemplary damages. The maximum award of damages under the Designs Act, 2000 is Rs.50,000/-. Section 55 of the Copyright Act, 1957, Section 108 of the Patents Act, 1970 and Section 135 of the Trademarks Act, 1999 do not specify the extent of damages which can be claimed, but rather, provide that this is subject to proof. How does one prove damages which cannot be calculated in terms of money? Can one quantify the loss that occurs to a person’s brand due to the fact that someone else has infringed his mark, broken into his market share and probably achieved considerable distinction and reputation in the market?

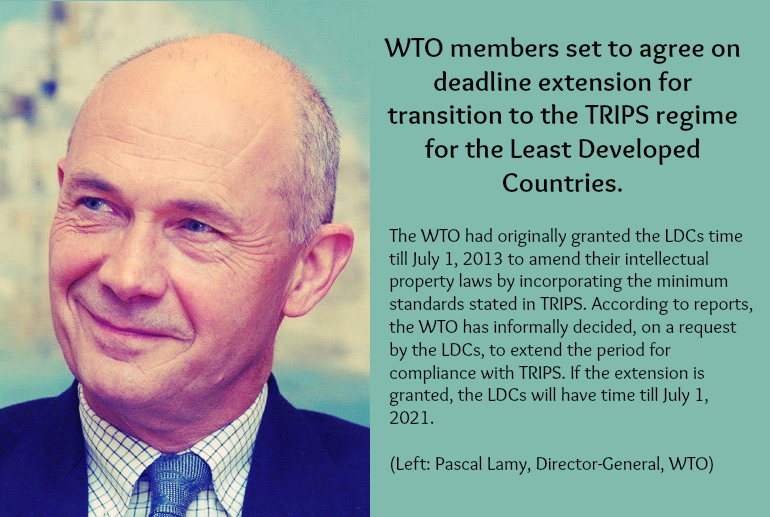

The decision would also go against the principles of the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPS”) as it mandates effective remedies to prevent IPR infringement. The absence of a temporary injunction would definitely mean lesser protection, and an effective remedy is lost to the person who seeks the relief.

Enforcement of the law would suffer. It would encourage parties to ‘take a chance’ and violate intellectual property rights and gamble at the trial. It would provide an incentive to the defendant to adopt dilatory tactics to delay the trial.

A speedy trial in IPR matters – is it a feasible approach?

The decision in Shree Vardhaman mandates that once the hearing of the matter commences, the suit should commence on a day-to-day basis, and that the final judgment should be delivered within 90 days of the filing of the suit.

Apart from the burden on our courts, these instructions are not mindful of a few factors.

Service to the defendant: Once a suit is filed, the suit summons need to be served on the defendant. If there were an ex-parte injunction in operation, in most cases, the defendant would come running to court. If there is no injunction rule in operation, the defendant will avoid summons for as long as possible. This can prolong matters for a few months, if not years.

Time for filing a written statement: Under the Civil Procedure Code (“the CPC”), the defendant has the right to have three months to file a written statement. Further, since the provision is merely directory and not mandatory, the defendant’s right to file a written statement is not lost even after 90 days. (See, Smt. Rani Kusum v. Smt. Kanchan Devi, AIR 2005 SC 3304). If there is no threat of an interlocutory injunction, the defendant can use every trick in the book (read CPC) to delay the inevitable. He can seek time for the inspection of documents, notice to admit documents, file interrogatories, take procedural objections, and file an application to reject the plaint.

Time for framing issues: After pleadings are complete, the court has to draft issues. Typically, the drafting of issues is something which is of the least priority to a court that is struggling with a huge pendency of matters. Even assuming that the court drafts issues within a week of completion of pleadings, both parties have the right to seek the amendment or the striking off of issues, for which interlocutory applications may be filed. No court can legitimately refuse to entertain any such application on the ground that the Supreme Court has stated that the trial should be complete in four months.

Interlocutory applications for discovery and inspection: After the court frames the issues and posts the matter for trial, the parties have to file a list of witnesses and documents. In order to establish their case or defence, the plaintiff or the defendant may require several documents from the opposite party. Obviously, the legitimate objections of the other party will have to be heard. In some cases, commissioners would have to be appointed to seize and take inventory of articles. In some cases, some governmental authority or expert will have to be examined and summons have to be issued to such persons.

Drafting of evidence and conducting trial: The drafting of evidence in contested trial matters and especially in IPR matters, is also quite complicated. If the defendant has denied each and every allegation, proof has to be adduced by documentation. Documents pertaining to the origin of a mark, its distinctiveness and ownership have to be examined. In copyright matters, the origin of copyright and proof of adaptation will have to be established. In patent matters, technical experts will have to be examined. If the defendant has raised questions regarding the validity of a design, copyright or patent, the plaintiff may be required to do considerable homework to dig up documents to prove and establish its case. These cannot be done over a period of a few weeks or months. In some matters, months will be required to prepare evidence and also to cross-examine witnesses. In these circumstances, it is necessary to give parties a fair opportunity to establish their case at trial. Enforcing a near impossible time-line would make it extremely difficult for parties (and to their counsel).

Delivering a judgment: Most judges in India are not specially equipped to handle IPR matters. To impose a strict timeline would only lower the quality of judgments delivered.

Appeals: Order 41 Rule 5 of the CPC says that the appellate court may stay proceedings. A stand may be taken that if there was no injunction granted in the first place, no additional harm will be caused if the execution of the decree is stayed for the duration of the appeal. In fact, even before the appeal is filed and immediately after the judgment is pronounced by the trial court, Order 41 Rule 5 (2) provides that the trial court may itself stay the operation of the decree. If injunctions should not be granted and the suits must be finally disposed of, then would that logic not apply to appellate courts as well?

Recently, Justice Krishna Iyer, while commenting on the Commercial Courts Bill, suggested that India was veering towards speedy justice only for the rich. Similarly, these judgments of the Supreme Court have sought to make a classification for the speedy disposal of all IPR matters. Instead of taking steps to improve judicial administration over all, this ad-hoc method of restricting the grant of temporary injunctions and seeking an early disposal of suits in specific matters is a dangerous precedent.

There have been several IPR cases where the Supreme Court has found a balance of convenience in favour of the defendant and therefore has not interfered and sought final disposal of matters by the trial court. These include cases where the defendants were established businesses, and the Supreme Court declined to make observations on the prima facie case. It was the subjective satisfaction of the court that made the court adopt such a measure. However, in light of the reasons suggested above, it would not be a good idea to adopt the same as a general rule.