Most game theory discussions start with an explanation of the “prisoners dilemma”. If only for the sake of originality (and since we will be coming back to the prisoner’s problems), let us start with a different ‘game’, the “driver’s dilemma”.

Most game theory discussions start with an explanation of the “prisoners dilemma”. If only for the sake of originality (and since we will be coming back to the prisoner’s problems), let us start with a different ‘game’, the “driver’s dilemma”.

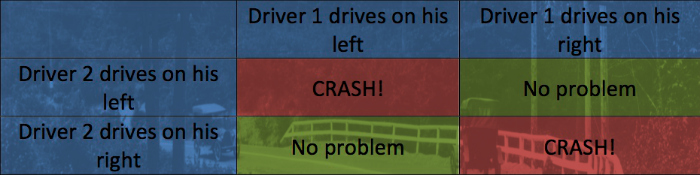

Imagine a world with no traffic rules. A driver can choose to drive on either the left or the right side of the road. Now, think of two drivers approaching a bend in the road from opposite directions. Since the road is curved, neither can see which side of the road the other is on. If both of them are on the same side of the road, they will crash into each other. If they are on opposite sides, they will pass each other with no incident. The following table shows the potential payoffs in this interaction.

Driver’s dilemma – No traffic rules

In a world with no rules, there is a 50 per cent chance that a driver will drive on the right and an equal chance that he or she will drive on the left. Since the individual driver cannot know the other driver’s choice, there is now a 50 per cent chance that they will both chose the same side and a 50 per cent chance that they won’t. And this means a 50 per cent chance of a crash each time they round a corner.

But if there were a law that fined drivers USD 500 for driving on the right, then all rational drivers would chose to drive on their left, thereby avoiding crashes.

Achieving beneficial outcomes for the group by aligning individual incentives

Game theory shows that a collection of individuals often act rationally and yet end up with outcomes that are bad both for the individual and for the group. In these situations, laws can be used to align individual incentives, for instance, let everyone agree on a side to drive on. This in turn leads to outcomes that are beneficial to the individual and to the society. Game theory frameworks can be used to identify areas where laws are necessary. Indeed, game theory justifies the very existence of laws in a free society!

Laws are designed to help individuals interact with each other productively to create successful societies and game theory is the study of how individual interactions add up to group outcomes. Game theory frameworks therefore, can be applied to a variety of legal questions.

For example in tort law, game theory can assist lawmakers and judges in setting punitive damages for defective products so as to incentivise manufacturers to establish the correct quality procedures. Game theory is also useful in intellectual property cases where regulators must balance the need to reward innovation (patent protection) against the necessity to make the innovation widely available (allowing generics). However, the most commonly discussed application of game theory in legal questions is the use of game theory in leniency policies, especially in the realm of antitrust enforcement.

Busting cartels and conspiracies using leniency

Broadly speaking, a leniency policy is an agreement that a member(s) of the conspiracy who assists law enforcement in proving a conspiracy will be given a reduced punishment, or perhaps no punishment at all.

When law enforcement investigates a crime, they usually suffer from an information asymmetry, that is, the conspirators know more than the enforcers about how the crime was committed. If the conspirators co-operate, then it becomes very difficult for law enforcement to obtain the proof they need to prove the conspiracy. By offering reduced punishments, leniency systems can give individual conspirators an incentive to ‘betray’ the conspiracy. This in turn provides enforcers with the necessary information to prove the conspiracy and punish the participants.

To illustrate how a leniency system can be an effective tool for law enforcement, let us use that canonical example of game theory, the “prisoner’s dilemma”.

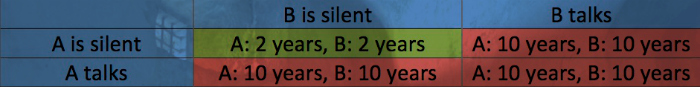

First, consider a system without a leniency policy. Two criminal accomplices (A and B) have conspired in a serious crime that carries ten years in prison. The police however, have evidence of only a minor crime punishable by only two years in prison. The police need information from at least one of them to have proof of the serious crime. The table below describes each person’s payoffs in this scenario.

Prisoner’s dilemma – no leniency

In this scenario, both A and B will clearly stay silent. In any scenario other than both staying silent, they both get 10 years in prison. So without a leniency policy, neither will co-operate and law enforcement is unable to prove the major crime.

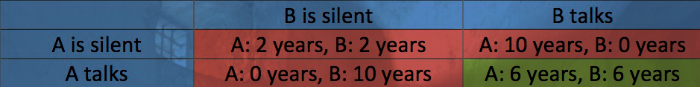

Now, what if the police were to offer some ‘leniency’ for cooperation. Both criminals will be offered a chance to confess. If one confesses while the other stays silent, the confessor will go free while the non-cooperator will get the maximum 10 years. However if both co-operate, both can get a reduced sentence of 6 years. The table below describes the payoffs in the revised scenario.

Prisoner’s dilemma – with leniency

In the revised scenario, if B is going to be silent, A is better off talking because A would go free. If B is going to talk, A is again better off talking since a six-year sentence is better than a 10-year sentence. So whatever B does, it is better for A to talk, so as a rational person, A will talk. However, if B is equally rational, he will talk as well. With both confessing, law enforcement can convict both for the serious crime.

This shows that leniency policies can be a powerful tool for law enforcement to break criminal conspiracies like cartels. For one, they provide the possibility of detecting conspiracies that might have gone undiscovered. Secondly information gleaned through the leniency system make it much more likely that the conspiracy can be proven and the participants sanctioned.

Perhaps more importantly, leniency policies act as a deterrent for conspiracies. If each conspirator knows that their partner has an incentive to betray them in the future, they are less likely to enter into the conspiracy to begin with. This is especially true when leniency is offered only to the first conspirator to come forward, creating a potential ‘race to betrayal’. Promoting confusion and mistrust in a conspiracy through leniency policies makes it less likely that a conspiracy can form or continue for long periods.

Leniency systems however, are no magic bullet. A leniency policy without a strong enforcement and investigative program for example, is toothless. Unless one or more conspirators fear imminent detection, they will have no incentive to come forward. Similarly, the level of punishment and leniency matter. If sanctions for conviction are minor, then it reduces the value of the leniency in coming forward.

Too much leniency however, means reducing the deterrent for forming conspiracies in the first place. At times, leniency policies can provide incentives for false testimony or even encourage the formation of cartels in certain situations. The specifics are important and game theory frameworks can be very useful in calibrating leniency policies. The dynamics of how game theory is used in setting the optimal policies for different situations is a fascinating discussion in itself. But to quote the famous Kipling, ‘that is another story for another time’.

Law enforcement uses leniency systems in a variety of contexts. The most common version is similar to the “prisoner’s dilemma” and a staple of most cop TV shows, where investigators urge a criminal ‘to roll’ on his accomplices. Whistleblower laws that reward employees for reporting malfeasance by their employers is another form of leniency policy. Perhaps the most discussed application of leniency policies is in investigating cartels of companies indulging in anti-competitive activities like price-rigging. Cartels are often very difficult to prove because much of the collusion between the firms is tacit and undocumented. This makes it crucial to have ‘inside info’ from one of the participants. A famous recent example was when Samsung was granted immunity by the European Commission for revealing a conspiracy with other firms like LG to collude on the prices of LCD screens. However, while it is a powerful tool, it must be used judiciously because there is much potential for abuse or for creating an environment where law enforcement seems inconsistent and arbitrary.

(Shree is a wandering economist who has changed his address fourteen times in the last fourteen years. He has few ideas except those opposite to who he is talking to.)