Loan agreements, like most commercial agreements, have a standard structure that must be moulded and adapted to suit specific transactions. In corporate lending, that is, where a bank is lending to a company, the amounts involved tend to be substantial and both the bank and the borrower will typically have legal representation. The bank’s lawyers usually draft the first version of the loan documents and the borrower’s lawyers review and negotiate the terms of the agreement on behalf of the borrower.

Loan agreements, like most commercial agreements, have a standard structure that must be moulded and adapted to suit specific transactions. In corporate lending, that is, where a bank is lending to a company, the amounts involved tend to be substantial and both the bank and the borrower will typically have legal representation. The bank’s lawyers usually draft the first version of the loan documents and the borrower’s lawyers review and negotiate the terms of the agreement on behalf of the borrower.

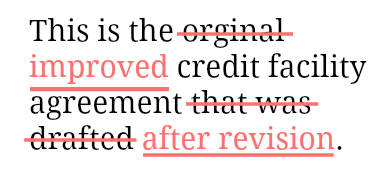

Remember, a loan agreement goes through many rounds of discussions and negotiation. A drafting lawyer must be prepared to rework the draft several times.

Term sheet

Before the lawyers begin drafting, the bank and the borrower enter into a term sheet that lays down the key commercial points that they have agreed upon in relation to the loan. Referred to as a financing term sheet, it is the basis for the legally binding documents that the lawyers have to draft. Generally, it covers only the more important aspects of a deal, without going into every detail covered in a binding contract. Typically, the authority or committee within a bank that reviews and approves loan proposals also considers financing term sheets.

Facility agreement

Often, a corporate loan is also called a ‘facility’ provided by the bank to the borrowing company and so, a corporate loan agreement is also known as a facility agreement.

A facility agreement between the bank and the borrower sets out the terms laid out in the term sheet in the form of a binding legal agreement. It contains the details of the loan, the manner in which the loan will operate, and the terms and conditions that have to be fulfilled by the parties to the agreement.

Each facility agreement is different and is drafted bearing in mind the nature of the facility. While there are several ways of drafting facility agreements, all of them can be divided into the following key sections—introductory, interpretation, operational, terms and conditions, and boilerplate clauses.

The introductory section

At the beginning of a facility agreement, the introductory section contains all the vital information that sets up the contract. This is typically the part where the drafter tells the reader what is being communicated, and what will be contained within the body of the contract.

At the beginning of a facility agreement, the introductory section contains all the vital information that sets up the contract. This is typically the part where the drafter tells the reader what is being communicated, and what will be contained within the body of the contract.

The title, the exordium, the recitals, and the table of contents, which are items that are found at the beginning of most commercial agreements, are placed at the beginning of a facility agreement also.

The interpretation section

Every facility agreement also needs a separate section defining the special terms used in the agreement, or terms that are used in a particular way in the agreement. Typically, in facility agreements in India, definitions are provided at the beginning.

This section should be accurately drafted as it will significantly impact the way in which key clauses in the agreement operate. Many definitions are common to all facility agreements, but they can have minor variations depending on the specific transaction. It is, therefore, important for the drafter to tailor the definitions to suit the term sheet.

Most facility agreements will define terms like “Borrower”, “Obligor”, “Material Adverse Effect”, and “Event of Default”. A drafter must examine the terms of the particular loan transaction and determine how they should be defined.

In addition to a definitions section, a facility agreement can also contain a section that sets out specific rules for interpreting the agreement. These rules apply through the document.

The operational section

This is the section of the facility agreement that deals with the operational details of the loan, that is, the amount of the loan, the term and purpose of the loan, how the loan will be drawn by the borrower, the repayment schedule, the details of payment of interest, conditions relating to prepayment of the loan, and so on. Obviously, these details are transaction-specific and the drafter will need to rely on the commercial understanding contained in the term sheet to draft the clauses in this section.

This is the section of the facility agreement that deals with the operational details of the loan, that is, the amount of the loan, the term and purpose of the loan, how the loan will be drawn by the borrower, the repayment schedule, the details of payment of interest, conditions relating to prepayment of the loan, and so on. Obviously, these details are transaction-specific and the drafter will need to rely on the commercial understanding contained in the term sheet to draft the clauses in this section.

Terms and conditions

The terms and conditions section of a facility agreement is transaction-specific and contains the terms and conditions based on which the lender agrees to give a loan to the borrower. These terms and conditions differ among agreements and include both generic conditions that any lender would ask of a borrower—such as the borrower’s capacity to take the loan—as well as conditions that specifically relate to the facts and circumstances of that particular facility. An example of a specific condition is one where the borrower has to obtain the necessary environmental approvals, if the loan is for setting up a power plant.

Broadly, the provisions in this section can be categorised as representations and warranties, undertakings, events of default, and consequences of events of default. This section also includes provisions protecting the bank from changes in circumstances that could affect the loan.

Representations and warranties

The representations and warranties in a facility agreement typically focus on issues such as:

– Whether the borrower is a legally incorporated entity, carrying on business legally, and is duly authorised to take the loan and enter into the agreement;

– Whether the loan agreement and other finance documents for the transaction will be valid, admissible as evidence, duly stamped or registered, and binding on the borrower;

– Whether the borrower has committed any default in relation to the loan or has committed any default that could impact the loan;

– Whether all the information, including financial statements, that the borrower provided to the lender, are true, accurate, and in the form that the lender requires;

– Whether the rights of the lender under the loan agreement or the security documents are in any way subordinated to any other creditor of the borrower;

– Whether the borrower has any legal proceedings pending against it that could affect the borrower’s business or its ability to repay the lender; and

– Whether the assets offered to the lender as security are legally owned by the borrower, and whether they are free of any existing encumbrances.

Covenants

Covenants or undertakings are provisions in the loan agreement that relate to actions that the borrower company is required to carry out (known as affirmative covenants), or prohibited from carrying out without obtaining prior consent from the bank (known as negative covenants). These can also be financial covenants, which set out parameters for the borrower to follow during the tenure of the loan. Typically, this section contains some specific financial definitions provided by the bank, based on which the bank intends to judge the financial performance of the borrower. The breach of these covenants can be an immediate event of default.

Events of default and consequences

The section on events of default tends to be extensive, in order to protect the interests of the bank in the best way possible. Broadly, events of default focus on the following key points:

The section on events of default tends to be extensive, in order to protect the interests of the bank in the best way possible. Broadly, events of default focus on the following key points:

– Events relating to the loan agreement: Naturally, any non-payment of any amount due to the bank, any breach of, or any misrepresentation under the loan agreement will be considered an event of default by the lender. Similarly, any breach, or misrepresentation in relation to the security documents will also be included as an event of default.

– Events relating to the borrower: There will also be some other events, which affect the borrower’s ability to repay the loan that will be included as events of default. These include cross-default provisions that consider non-payment by the borrower in other loans as a default, any events in relation to the insolvency of the borrower, the cessation of business by the borrower, any illegal activity by the borrower, and so on.

Since loan agreements tend to be fairly one-sided documents, where the obligations remain primarily on the borrower, events of default are usually linked only to breaches by the borrower and not by the lender.

Deeksha Singh is part of the faculty on myLaw.net.