Are orders and decisions of the Competition Commission of India (“CCI”) judgments in rem, or do they only bind the parties to a particular dispute? Take a scenario where the CCI has ultimately held that an agreement between X with Y is anti-competitive under Section 3 of the Competition Act, 2002.

Are orders and decisions of the Competition Commission of India (“CCI”) judgments in rem, or do they only bind the parties to a particular dispute? Take a scenario where the CCI has ultimately held that an agreement between X with Y is anti-competitive under Section 3 of the Competition Act, 2002.

1. Would the finding apply to an identical agreement between X and Z, which the parties entered into after the CCI made its finding? Would it apply to an identical agreement between X and P, which the parties entered into before the CCI’s finding?

2. Would the finding apply to identical or similar agreements between A and B, which the parties entered into, either before or after the CCI’s finding?

Section 3 of the Act which deals with anti-competitive agreements, Section 4 which deals with abuse of dominant position, and Section 6 which deals with the regulation of combinations, attempts to proscribe or forbid certain types of behaviour which have an adverse bearing on competition in the market. The focus is on the behaviour of the entities, as opposed to the entities themselves. It could be said therefore, that a finding that a certain clause or transaction or practice is anti-competitive or abusive could apply to third party enterprises indulging in identical or similar practices, even if they were strangers to the earlier proceedings. To that extent, it could be said that the CCI is laying down the law on legally acceptable behaviour in the market.

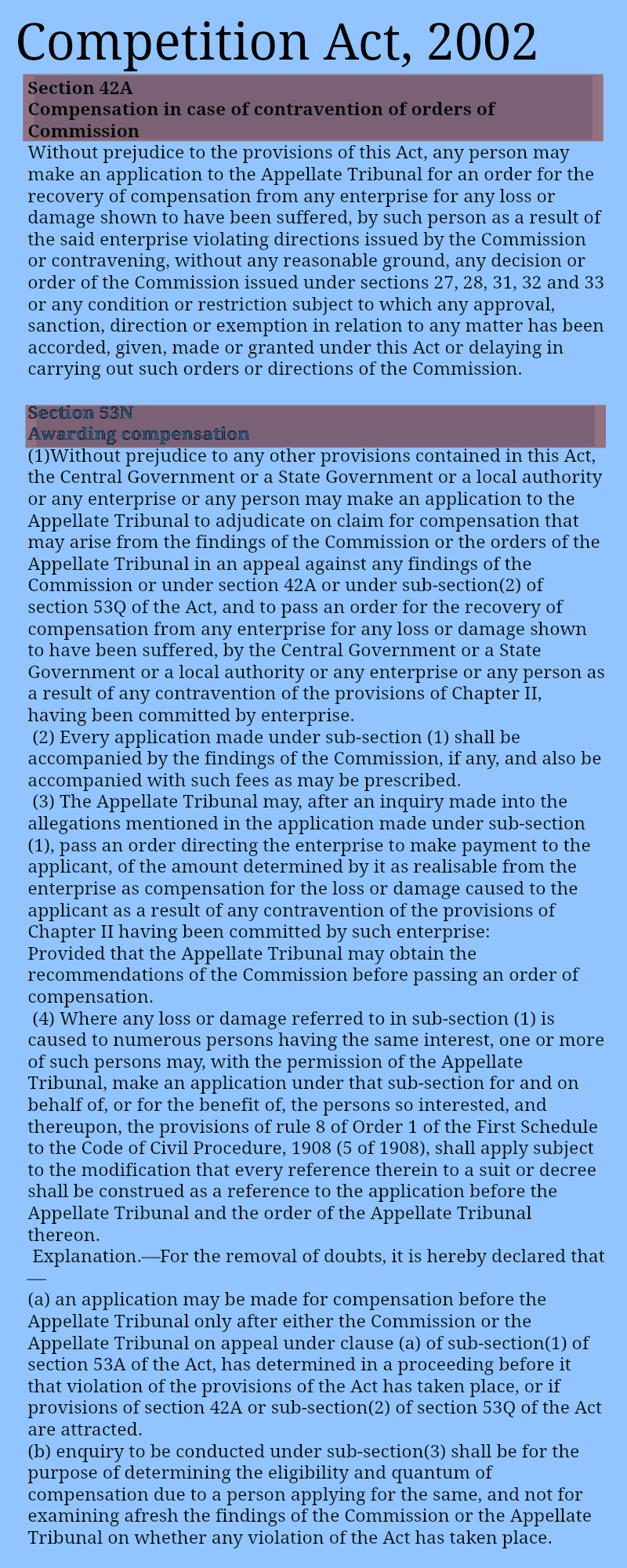

However, practically, does this mean the CCI can forego investigation and proceed to declare as anti-competitive, the agreements between X and Z, or X and P, or A and B? Sections 42A and 53N help address these questions.

Comparing Sections 42A and 53N

Section 42A applies to the violation of specific directions or orders issued against a specific enterprise, whereas Section 53N applies to situations covered by Section 42A as well as to subsequent violations of Chapter II of the Act (which contains Sections 3, 4, and 6) by the same enterprise. In other words, the scope of Section 53N is broader. In both instances, the Competition Appellate Tribunal (“COMPAT”) decides applications for compensation.

Under both provisions, an application for compensation may be moved by “any person” who is aggrieved either by a violation of the CCI’s directions or orders by the enterprise against which they were issued, or by a violation of the Act itself by such an enterprise, subsequent to and prior to the date of its conduct being declared as anti-competitive by the CCI or the COMPAT.

Critically, Section 53N(1) read with the Explanation (a) to Section 53N answers the queries raised in the  post. An application for compensation against an enterprise such as X may be moved only after its conduct has been found violative of the Act either by the CCI orthe COMPAT. It can be moved by “any person” who has suffered damage or loss as a result of the conduct. Therefore, if X’s conduct in relation to Y has been found anti-competitive, and X has entered into identical or similar transactions with P and Z in the past or the future, Y,P, and Z may all apply to COMPAT for compensation against X.

post. An application for compensation against an enterprise such as X may be moved only after its conduct has been found violative of the Act either by the CCI orthe COMPAT. It can be moved by “any person” who has suffered damage or loss as a result of the conduct. Therefore, if X’s conduct in relation to Y has been found anti-competitive, and X has entered into identical or similar transactions with P and Z in the past or the future, Y,P, and Z may all apply to COMPAT for compensation against X.

However, as the explanation implicitly clarifies, the finding with respect to X’s conduct cannot be directly applied or extended to an agreement between A and B, even if the agreement is identical or similar to the X’s agreement with Y, until it is determined afresh by the CCI or COMPAT (in appeal) that such agreement between A and B is violative of the Act.

Simply put, if the conduct of a party has been found to be violative of the Act, the Commission need not revisit the illegality of the party’s conduct over and over again in order to award compensation to parties affected by the party’s conduct. However, if a stranger to the earlier proceedings indulges in identical or similar conduct, it needs to be investigated and a fresh finding must be arrived at.

Another important caveat is that if a party’s conduct involves abuse of dominance under Section 4 of the Act, it may not be possible to extend the findings arrived at in one case to past or future conduct since it would need to be ascertained if the party was in a position of dominance during each of the impugned transactions. This is because under Section 4, only the conduct of dominant parties may be investigated. Therefore, if a party is no longer dominant at the time of the subsequent transaction, the earlier finding may not be valid, which means a fresh investigation is necessary to arrive at the finding of abuse of dominance.

J. Sai Deepak, an engineer-turned-litigator, is a Senior Associate in the litigation team of Saikrishna & Associates. He is @jsaideepak on Twitter and the founder of “The Demanding Mistress” blawg. All opinions expressed here are academic and personal.