The previous post discussed the Supreme Court’s views in Enercon (India) v. Enercon GmBH (dated February 14, 2014) on how arbitration clauses ought to be interpreted. In this post, we will look at two other issues related to the arbitration clause – namely, the choice-of-law issues that the vaguely drafted Clause 18 (the arbitration clause) in the Intellectual Property Licence Agreement (“IPLA”) gave rise to, and the discussion on separability that the challenge to the IPLA led to.

The previous post discussed the Supreme Court’s views in Enercon (India) v. Enercon GmBH (dated February 14, 2014) on how arbitration clauses ought to be interpreted. In this post, we will look at two other issues related to the arbitration clause – namely, the choice-of-law issues that the vaguely drafted Clause 18 (the arbitration clause) in the Intellectual Property Licence Agreement (“IPLA”) gave rise to, and the discussion on separability that the challenge to the IPLA led to.

On the choice of seat

“18.3 All proceedings in such arbitration shall be conducted in English. The venue of the arbitration proceedings shall be London… The provisions of the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 shall apply.”

It is really difficult to work out what the parties intended when they were drafting this clause. Did they intend for London to be the seat, using the word “venue” as an alternative for “seat”? But if that were the case, why insert the words, “The provisions of the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 shall apply”? Was it merely a reference to Part II of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, inserted to ensure that an English award is enforceable in India? It is a very real possibility, as many India related foreign-seated arbitration clauses expressly include the application of Part II (and expressly exclude Part I).

The net result of this clause was confusion about what the seat was, whether the seat was different from the curial (that is, procedural) law, and what the law governing the arbitration agreement was.

On this point, we are not entirely in agreement with the reasoning of the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court believed that the parties had made no choice on the seat. They disregarded the language “The venue of the arbitration proceedings shall be London” holding that this sentence only indicated the parties’ choice of a convenient “venue” for their hearings, never mind the fact that there was no indication in the current case that suggested that London would be convenient. The obiter views of Eder J. in the English High Court proceedings in the same case, [2012] EWHC 689 (Comm), illuminate this point.

“London was not a convenient geographical venue for disputes concerning an Indian joint venture; intellectual property in India; an Indian and German company; where the evidence would be located in India and possibly to some extent in Germany. In my judgment, the designation of London therefore had to have some other function for it to be explicable.”

Having decided that the parties had only designated a venue and not a seat in Clause 18.3, the Supreme Court went on to consider the jurisdiction with which the arbitral proceedings had its closest connection – the ‘closest connection’ test is what is generally used by tribunals and courts to determine the seat in the absence of a choice by the parties. The Court cited Dicey and Morris on the Conflict of Laws in this regard.

This is where things get murky. The Court seems to assume that the words, “The provisions of the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 shall apply” indicate that the parties have chosen Indian law to govern the arbitration, that is, they have chosen Indian law (including Part I of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996) as the “curial” or “procedural” law. Having come to the conclusion that the procedural law was Indian law, the Court found that designating London as the seat would lead to an absurdity – as Part I of the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 cannot apply to a foreign-seated arbitration (following BALCO), and further, English law itself does not allow for the procedural law to be different from the law of the seat. In other words, the designation of London as a seat would render what the Court believed was the parties’ choice of curial law (the words “The provisions of the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 shall apply”) redundant.

As far as the proper law of the arbitration agreement was concerned, the Court understood this to be Indian law without too much reasoning on the point, although one can argue that the proper law of the arbitration agreement follows the substantive law of the contract (the NTPC v. Singer argument) and as Indian law was the governing law of the IPLA (Clause 17), the proper law of Clause 18 should also be Indian law.

Having worked out that the curial law, the proper law of the arbitration agreement, and the governing law were all Indian law, the Court held that the seat should also be India, as the arbitration as a whole has its closest connection with India.

While we agree that the arbitration had its closest connection with India, we are not sure that there was a need to resort to this test in this first place. In other words, we do not entirely agree with the Court’s dismissal of the commonsense understanding of the parties’ designation of London as the “venue” to mean the “seat”, especially in light of the fact that London would not have been a “convenient” geographical venue.

The Court also discussed and distinguished several English judgments that supported the argument that the words, “The venue of the arbitration proceedings shall be London”, indicated the parties’ choice-of-seat.

One very similar case was Shashoua v. Sharma [2009] EWHC 957, where Cooke J. had held that in an ICC arbitration clause that provided that “the venue of arbitration shall be London, United Kingdom”, meant that London was the juridical seat and English law was the curial law.

“When therefore there is an express designation of the arbitration venue as London and no designation of any alternative place as the seat, combined with a supranational body of rules governing the arbitration and no other significant contrary indicia, the inexorable conclusion is, to my mind, that London is the juridical seat and English law the curial law…” (Para 30)

The Supreme Court believed that this reasoning was not applicable in the Enercon case, as the parties had not designated any supranational body of rules like the ICC Rules to govern the arbitration; instead they had chosen the India’s arbitration statute (Para 118). This reasoning (for distinguishing Enercon from Shashoua) is not entirely convincing.

Another case worth mentioning is Union of India v. McDonnell, [1993] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 48 where, similar to the Enercon clause, the arbitration agreement contained conflicting provisions: “The arbitration shall be conducted in accordance with the procedure provided in the Indian Arbitration Act of 1940 …” and “The seat of the arbitration proceedings shall be London, United Kingdom.” Saville J. held that the reference to the Indian Arbitration Act, 1940, did not have the effect of changing the “seat” designated by the parties. Rather, the phrase was only a reference to the internal conduct of the arbitration. The Supreme Court mentions this case in Para 119, but does not really distinguish it.

The Court also discussed a few other recent English cases on the proper law of the arbitration agreement and the “closest and most real connection” test (we have discussed these at length in a previous post). We won’t spend too much time on all the cases discussed by the Court (Paras 100 to 125) – but it is interesting to note that the Court seems to use the test prescribed in these cases on the proper law of the arbitration agreement – to work out the choice-of-seat.

The assumption that the parties designated Indian law as the curial law is also curious, and there is not enough discussion in the judgment on the possible alternative constructions of the sentence, “The provisions of the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 shall apply”. It can be read as referring simply to Part II of the Indian 1996 Act, that is, the enforcement provisions, which is something international arbitration clauses often have to clarify.

On separability

One of the issues in dispute was whether the IPLA was a valid and enforceable contract. Enercon India argued that the IPLA had not been executed properly and on this basis, argued that the arbitration agreement, which was contained in Clause 18 of the IPLA, was also not valid or enforceable.

The Supreme Court dismissed this argument and rightly so. The Court discussed how Enercon India’s argument was not that the arbitration agreement was “null and void, inoperative and incapable of being performed” (Section 45) but that “ the matter cannot be referred to arbitration as the IPLA, containing the arbitration clause/agreement, is not a concluded contract.” (Para 75)

The logical leap Enercon Indian made in making that submission was incorrect as the arbitration agreement is a separate agreement (‘separate’ from the underlying contract) that is not affected by the lack of validity of the underlying contract. Here, there was absolutely no question that the arbitration agreement alone (that is, Clause 18) was agreed to by the parties (Para 76). Accordingly, the arbitration agreement in this case was valid, and unaffected by any ruling to the contrary in relation to the IPLA.

The logical leap Enercon Indian made in making that submission was incorrect as the arbitration agreement is a separate agreement (‘separate’ from the underlying contract) that is not affected by the lack of validity of the underlying contract. Here, there was absolutely no question that the arbitration agreement alone (that is, Clause 18) was agreed to by the parties (Para 76). Accordingly, the arbitration agreement in this case was valid, and unaffected by any ruling to the contrary in relation to the IPLA.

Since the validity of the IPLA was a substantive issue in dispute and formed part of the parties’ reference to arbitration, the Court left this issue to be decided by the arbitral tribunal in accordance with this arbitration agreement.

Drafting lessons

The drafting lessons from Enercon are fairly simple and easy to implement, but, as this dispute reflects, it is very important to get them right.

– One, specify the seat. And use the word, “seat”. This case, as well as the Shashoua case, highlights the confusion that can be caused by calling the “seat” by some other name.

– Secondly, think through the arbitral process that you spell out in your agreement. What is the appointment mechanism? Who appoints the chairman? Ensure that you don’t have an unworkable mechanism like under Clause 18.1 in this case — you don’t want to have to depend on a court to make sense of your drafting.

(Sindhu Sivakumar is part of the faculty on myLaw.net.)

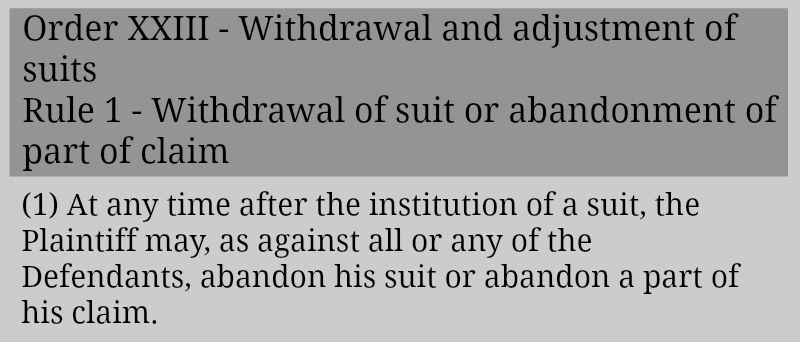

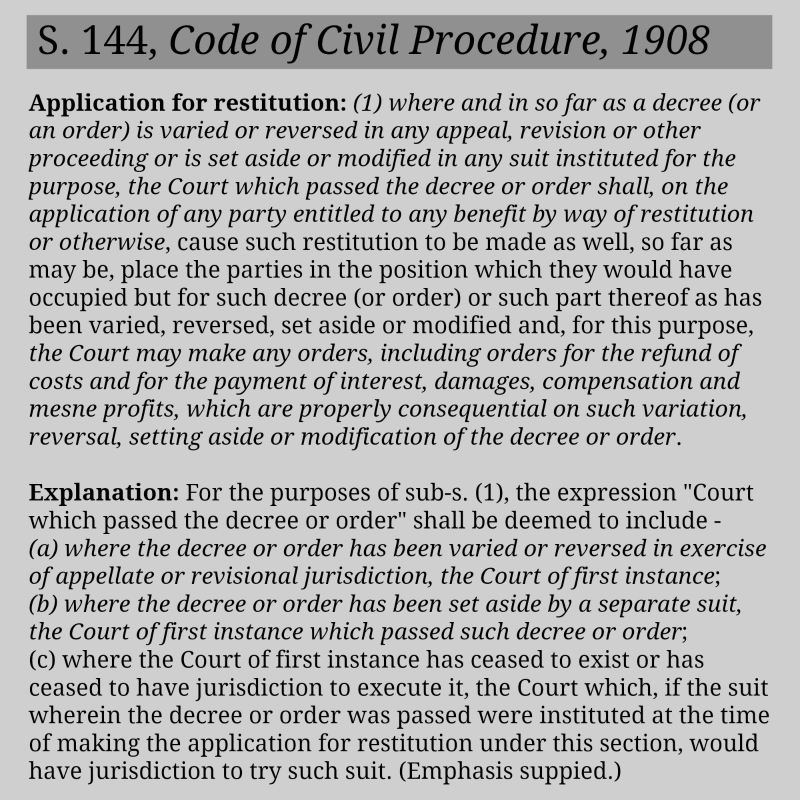

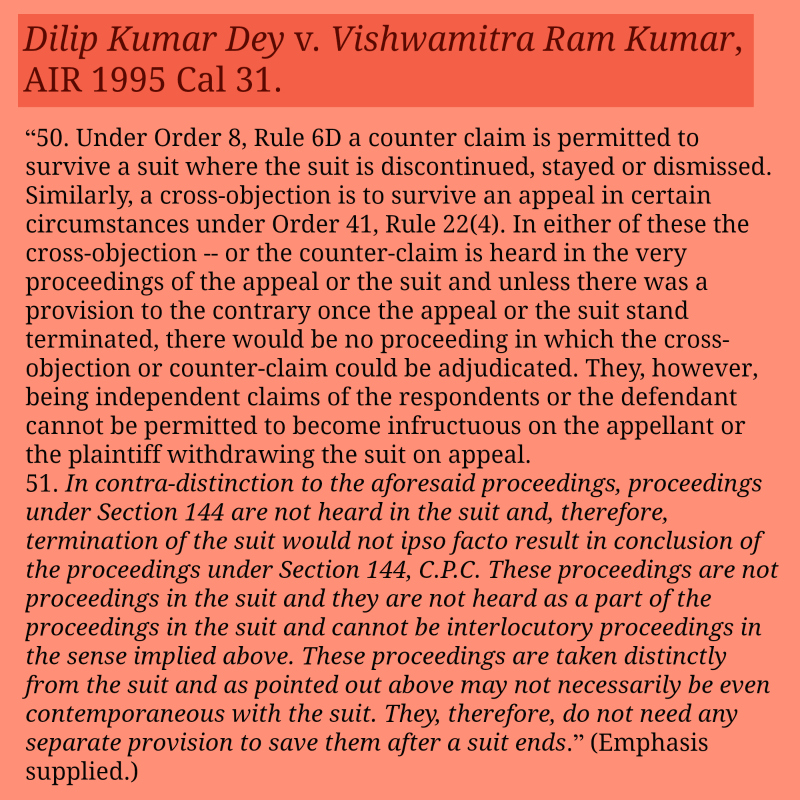

Can a patentee, after filing a suit for infringement and securing an interim injunction against the defendant, withdraw the suit at will? Interim orders after all, are granted only on a prima facie appreciation of the case and the result at the end of the trial could well be in favour of the defendant. Can the plaintiff therefore, be permitted to withdraw the suit at will without affording the defendant an opportunity to establish his case at trial? Also, since interim orders could have caused significant injury or loss to the defendant, can the defendant not legitimately expect restitution for the loss suffered by him? These questions are not answered by the Patents Act, 1970, but instead, require us to look into the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (“CPC”).

Can a patentee, after filing a suit for infringement and securing an interim injunction against the defendant, withdraw the suit at will? Interim orders after all, are granted only on a prima facie appreciation of the case and the result at the end of the trial could well be in favour of the defendant. Can the plaintiff therefore, be permitted to withdraw the suit at will without affording the defendant an opportunity to establish his case at trial? Also, since interim orders could have caused significant injury or loss to the defendant, can the defendant not legitimately expect restitution for the loss suffered by him? These questions are not answered by the Patents Act, 1970, but instead, require us to look into the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (“CPC”).