Recently, questions were raised about the powers of the police and the protections available to the accused when Delhi’s law minister Somnath Bharti, accompanied by members of his party and the police, conducted an impromptu ‘raid’ on the residence of some African nationals, most of them women. Mr. Bharti supposedly took the drastic step — a raid without a warrant —following alleged police negligence of complaints made by other residents of the neighbourhood, of a drugs-and-prostitution racket in the locality.

Recently, questions were raised about the powers of the police and the protections available to the accused when Delhi’s law minister Somnath Bharti, accompanied by members of his party and the police, conducted an impromptu ‘raid’ on the residence of some African nationals, most of them women. Mr. Bharti supposedly took the drastic step — a raid without a warrant —following alleged police negligence of complaints made by other residents of the neighbourhood, of a drugs-and-prostitution racket in the locality.

Two statutes — Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 (“NDPS Act”) and the Prevention of Illicit Traffic in Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1988 (“PITNDPS Act”) — govern the offences of the consumption, illegal manufacture, illegal trade, and illegal distribution of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances in India. The NDPS Act defines offences, prescribes the procedure for investigation including searches, seizure, and arrests, and provides for punishments for each offence. The PITNDPS Act focuses on detention orders.

Both statutes are considered draconian and Indian courts have had to read down their stringent provisions often. For instance, ‘minor offences’ — those offences under the NDPS Act that carry punishments of jail terms less than three years —are now considered “bailable” by the Bombay High Court. In another landmark pro-rights’ judgment, the Bombay High Court found that Section 31-A of the NDPS Act, which provides for the death penalty in certain situations, did not measure up to the procedural safeguards envisaged by the Constitution. It is interesting to note that almost 32 countries in the world prescribe the death penalty for drug related offences, and India is one of these.

Search under the NDPS Act

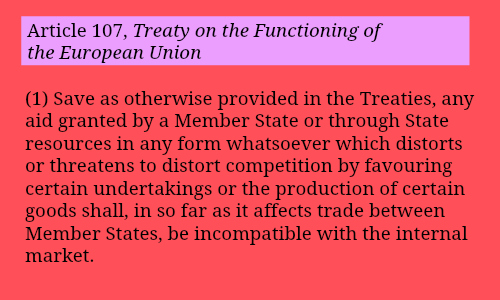

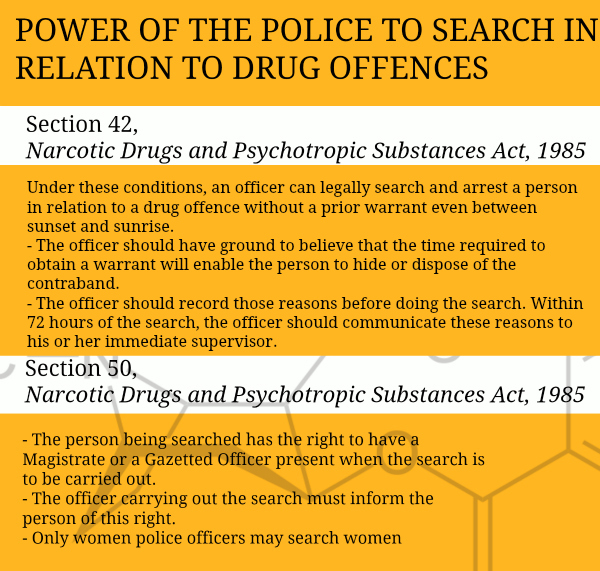

In the NDPS Act, Chapter V (Sections 41 to 68) enlists the procedure for searches, seizures, and arrests.  Under Section 42 — important in the recent context — an officer may search and arrest a person in relation to a drug offence without a prior warrant between sunset and sunrise, only if there is ground to believe that the time required to obtain such a warrant will enable the person to be searched to hide or dispose off the illicit items. In such a case, the officer carrying out the search needs to record his grounds for carrying out the search before conducting the search, along with the information on which his actions are based and send this to his superior officer within seventy-two hours. Section 43 of the NDPS Act provides for searches and seizures in public places (such as hotels and modes of conveyances).

Under Section 42 — important in the recent context — an officer may search and arrest a person in relation to a drug offence without a prior warrant between sunset and sunrise, only if there is ground to believe that the time required to obtain such a warrant will enable the person to be searched to hide or dispose off the illicit items. In such a case, the officer carrying out the search needs to record his grounds for carrying out the search before conducting the search, along with the information on which his actions are based and send this to his superior officer within seventy-two hours. Section 43 of the NDPS Act provides for searches and seizures in public places (such as hotels and modes of conveyances).

Article 22 of the Constitution of India encapsulates the fundamental rights of an arrested person to be informed of the grounds for an arrest, to be produced before a Magistrate within twenty-four hours, and to mount a defence. This constitutional protection finds application in the NDPS too.

Under Section 50, a person has the right for the search to be conducted in front of a Magistrate or a Gazetted officer. Further, the officer carrying out the search must inform the person being searched of their right to have a Magistrate or a Gazetted Officer present when the search is to be carried out. Moreover, all searches of persons must be done after they have been clearly informed of their rights. Recently in Vijaysinh Chandubha Jadeja v. State of Gujarat, (2011) 1 SCC 609, the Supreme Court stated that any conviction based on the recovery of an illicit item in a search conducted without informing the accused of this right would stand vitiated. It is also a legislative requirement under Section 50(4) that only women police officers may search women.

Protections during arrest

Under Section 42 of the NDPS Act, a person may be arrested without a warrant, on the suspicion of the commission of a drug-related offence. Such an arrest, however, must be immediately followed by the provision of a written order outlining the grounds of arrest and the production of the arrested person before a Magistrate.

The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (“CrPC”), sets out the general criminal procedure related to most penal offences and fills in the gaps left by the NDPS Act and the PITNDPS Act. Under the CrPC, an arrest may be made by a junior police officer without a valid warrant upon a written order containing the substance of the order for arrest. The person under arrest must be produced before a Magistrate without delay and under Section 41(1)(a) of the CrPC, a person may be arrested without a warrant if there exists ‘reasonable suspicion’ of such a person being ‘concerned’ in a ‘cognizable offence’ (where arrest may be made without a warrant). Needless to say, offences under the NDPS are cognisable.

Extra-judicial testing

In recent times, India’s domestic law enforcement has shown signs of disquieting vigilantism. It is a common practise during raids for the police to require all persons present at the venue of the raid to submit to blood or urine tests. This practise is completely extra-judicial. There is no mention in the NDPS or in the PITNDPS of the immediate testing of a person in relation to a drug-offence. Unlike some other laws, such as the Motor Vehicles Act, 1939 that provides for testing for the presence of alcohol in offences of drunk driving, there are no legal provisions under the NDPS Act to permit testing for drug use.

In recent times, India’s domestic law enforcement has shown signs of disquieting vigilantism. It is a common practise during raids for the police to require all persons present at the venue of the raid to submit to blood or urine tests. This practise is completely extra-judicial. There is no mention in the NDPS or in the PITNDPS of the immediate testing of a person in relation to a drug-offence. Unlike some other laws, such as the Motor Vehicles Act, 1939 that provides for testing for the presence of alcohol in offences of drunk driving, there are no legal provisions under the NDPS Act to permit testing for drug use.

Time and again, the judiciary has asked for strict interpretation and application of stringent laws such as the NDPS, in order to minimise the risk of human rights’ violations. Body searches of an invasive nature, and sampling of urine or blood amount to a violation of the integrity of the human body. Such acts need to be authorised by law. Without specific provisions enabling such actions by law enforcement officials, investigations become fishing expeditions in the murky waters of human rights violations. Just last year, the Supreme Court laid down extensive guidelines on the interpretation and application of the legislative provisions relevant to testing such samples in Thana Singh v. National Bureau of Narcotics. The Court also highlighted the lack of adequate Central Forensic Science Laboratories that could possibly carry out such tests with minimal interference.

While the common practise of the law enforcement authorities to subject persons to such ‘tests’ without legislative or judicial authority is high-handed, it is yet to be more strictly monitored. On the other hand, a legal provision that regulates testing strictly in drug-related offences can also be a used by suspects, since innocence can then be proved on the basis of scientific fact.

Foreigner or not, it is important to know one’s rights when faced with accusations of having committed an offence under a strict legal machinery in place to combat drug trafficking. It is hoped that those tasked with formulating, upholding, and interpreting the law, ensure procedural safeguards at every stage of the criminal justice system in favour of the accused.

(Suhasini Rao is part of the faculty on myLaw.net.)

Note: The post has been edited once since publication.