Bangalore was the venue for an interesting event almost two weeks ago. The Global Bitcoin Conference was organised by the digital currency awareness organisation CoinMonk to highlight the importance of virtual or digital currencies. Bitcoin is the most prominent currency among these virtual currencies, that is, money that exists as computer code. Various stakeholders are keen on convincing the government and regulators that Bitcoin is a valuable economic innovation, and that it will not be used for illegal transactions.

Bangalore was the venue for an interesting event almost two weeks ago. The Global Bitcoin Conference was organised by the digital currency awareness organisation CoinMonk to highlight the importance of virtual or digital currencies. Bitcoin is the most prominent currency among these virtual currencies, that is, money that exists as computer code. Various stakeholders are keen on convincing the government and regulators that Bitcoin is a valuable economic innovation, and that it will not be used for illegal transactions.

What is Bitcoin?

Bitcoin is an open source, peer-to-peer, electronic cash system. It is software that allows the virtual currency named Bitcoin to be mined and stored in a personal Bitcoin wallet. It also allows users to send and receive Bitcoin(s). Bitcoin cannot be redeemed for another type of money or for a commodity, like gold. It is not backed by any government or other legal institution.

Traditional currency usually has the following features: scarcity, divisibility, portability, and easy storage. They are minted and issued by central banks of countries.

In the case of Bitcoin however, new Bitcoins are issued to competing ‘miners’ online. These miners solve problems using their computers and thus generate Bitcoin. A person can create unlimited free Bitcoin accounts. You can find a primer on the use of Bitcoins here.

The growing popularity of Bitcoin, since its inception in 2008, has resulted in the evolution of a number of entities such as exchanges, transaction services providers, and joint mining operations. It is now accepted by a number of service providers.

The growing popularity of Bitcoin, since its inception in 2008, has resulted in the evolution of a number of entities such as exchanges, transaction services providers, and joint mining operations. It is now accepted by a number of service providers.

In India too, Bitcoin has found a fair number of users. According to this article in the Mint, more than 24,000 people in India have downloaded Bitcoin in 2013 itself. While this number of users is nowhere close to countries like U.S., China, or Germany, there is enough activity to suggest that government and regulators in India should pay attention. The Reserve Bank of India (“RBI”) however, is yet to take a stand.

Is Bitcoin currency?

Earlier this year, a U.S. District Court in Securities and Exchange Commission v. Trendon T. Shavers, as part of a larger discussion, discussed whether Bitcoin is a currency. The court held that:

“It is clear that Bitcoin can be used as money. It can be used to purchase goods or services, and as Shavers stated, used to pay for individual living expenses. The only limitation of Bitcoin is that it is limited to those places that accept it as currency. However, it can also be exchanged for conventional currencies, such as the U.S. dollar, Euro, Yen, and Yuan. Therefore, Bitcoin is a currency or form of money, and investors wishing to invest in BTCST provided an investment of money.”

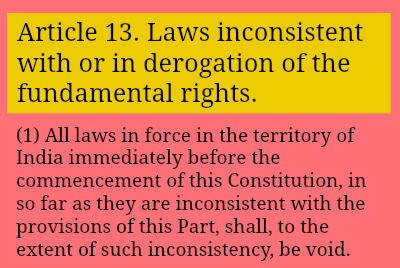

Now, in India, Entry 36 in List I in the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution of India, 1950 squarely places the power of making law on the subject of ‘currency, coinage, and legal tender’ with the Union Government. The RBI was formed under the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 (“RBI Act”) to take over the management and issue of currency from the Central Government. Section 22 of the RBI Act gives the RBI the sole right to “issue currency notes of the Government of India”. Interestingly, there is no definition of ‘currency’ or ‘currency notes’ in the RBI Act. At the same time, there is also no express prohibition on issue of ‘private currency’ by private entities.

There is a definition of currency in Section 2(h) of the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999, according to which ‘currency’ includes “includes all currency notes, postal notes, postal orders, money orders, cheques, drafts, travellers cheques, letters of credit, bills of exchange and promissory notes, credit cards or such other similar instruments, as may be notified by the Reserve Bank”. This means that until the RBI notifies virtual currencies as ‘currency’, the management and issue of Bitcoin remains legally, a grey area.

The RBI is certainly aware of the existence of, and the risks involved with virtual currencies. While it has stated that the absence of a distinct legal framework means that the traditional rules of financial sector regulation and supervision are not involved, it has remained silent on what rules need be evolved to deal with such currencies.

That the regulation of Bitcoin and other virtual currencies is necessary is obvious even from a cursory examination of the legal issues it throws up. For example, a question similar to the issue in the Shavers case mentioned above, is whether Bitcoin investments in Indian entities will be considered ‘securities’? What about the ramifications on foreign exchange management and regulation? To quote this article, the use of Bitcoin can significantly reduce the costs of transferring U.S. dollars across the border from India. Of course, the opportunities for the use of such a currency—which is fungible with other currencies but is not owned or regulated by any government or legal entity—provides huge avenues for money laundering and use in illegal activities.

So, as the number of Bitcoin users in India increases and Bitcoin exchanges like Buttercoin gear up to start operations in India next year, the RBI (which has currently adopted a wait-and-watch policy) will need to clarify its position sooner rather than later.

(Deeksha Singh is part of the faculty on myLaw.net.)